Political Science Courses by Fields (Old)

Change to new tracksQuick Jump to Fields of Study:

Introduction

The University of Rochester's program in political science helps students understand processes and outcomes of political conflict both from an abstract theoretical perspective and as explored systematically in a wide variety of real-world settings--not only in American governmental institutions but also in global warfare, international trade, and social movements, for example.

The faculty at the University of Rochester are highly acclaimed for their research. Our department is regularly ranked in the top handful of political science departments in the country. Our faculty include two past presidents of the American Political Science Association, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, three fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the former Managing Editor of the American Political Science Review, Guggenheim fellows, Fulbright scholars, a visiting scholar at the Russell Sage Foundation, and two fellows at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Professors Fenno and G. B. Powell have each won the Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award, given for the year's best book in political science, and department faculty regularly publish in the discipline's most prestigious journals. In 2009 and 2010 Professor Meguid won three awards--in political economy, European politics, and European studies--for her book analyzing the relationship between niche parties and mainstream parties. Professor Primo's book on budgets and legislative rules won the 2008 prize recognizing work of practical importance for legislators. Over the last few years, Professor Gamm's book on Boston's urban exodus was recognized as the year's best book in community and urban sociology and the year's best book on contemporary Jewish life in the United States, Professor Fenno's book on changing styles of representation was recognized as the outstanding book in Southern politics, Professor G. B. Powell's book on the electoral foundations of democracy was recognized as the year's best book in comparative politics, and Professor Stone's book Lending Credibility won the Ed A. Hewett Book Prize.

We are proud of our reputation as top researchers. We are equally proud of our accomplishments as top teachers in one of the most popular undergraduate majors in the College and in one of the nation's leading PhD programs. In 2005 the Political Science Department received the College's highest honor for excellence in undergraduate education, receiving the Goergen Prize for curricular achievement. Four faculty in the department--Professors Gamm, Johnson, Primo, and G. B. Powell--have won the University's Goergen Award for "distinguished achievement and artistry in undergraduate teaching." Professor Primo has also received the Students' Association award as the College's outstanding professor of the year, and Professor Signorino received the University-wide Curtis Prize in recognition of his work as a graduate and undergraduate teacher. And Professors G. B. Powell and Niemi have each received the William H. Riker University Award for Excellence in Graduate Teaching. We have a strong commitment to both undergraduate and graduate education. We know well that research and teaching go naturally together: the creation and dissemination of knowledge are two sides of the same coin.

Where can an undergraduate go with a political science degree? In addition to providing instruction in "a science of politics," a major in political science at the University of Rochester provides students with strong training in the valuable skills of writing, communications, and analytical thinking that are integral to a liberal arts education and are an excellent preparation for a variety of careers. Political science is also a good preparation for participation in community organizations, electoral politics, and movements to support specific policies. Not least of all, political science also has a specific professional application-in the sense that its object of study is of particular interest to those planning a career in law, government, or journalism.

Fields in Political Science

Political scientists are a diverse lot, and the faculty and courses at the University of Rochester reflect this fact. While the effort to generalize about politics is found in all courses in political science offered in the College, there is a wide variety of theoretical perspectives and substantive content. This variety is partly reflected in the organization of our courses into different fields. These fields of political science, described below, are widely used by political scientists to describe their general areas of interest and expertise.

You may already know you have a strong interest in a particular field or fields, but it is also likely that you are unfamiliar with many of them. To introduce you to the diversity that makes up political science, we require undergraduates to sample courses from at least four fields--but we also allow you to specialize. In fact, this notion is a basic organizing principle of the major in political science: you must sample, but you may specialize. We think the combination works. It exposes you to a variety of perspectives and substantive knowledge, all of them part of political science, and then allows you to explore a field or fields in greater depth, based on your own particular interests. For a complete list of requirements for undergraduate and graduate degrees, see information for undergraduates and graduate students.

Note on Courses

The courses of instruction listed below constitute a complete list of courses currently offered. Many courses are linked to syllabi, usually representing the most recent time that a course was taught. Not every course is offered every year, and new courses are constantly added to this list. The department's website also contains lists of courses offered this semester and next semester, including full course descriptions.

Courses offered in past years are not listed below if they are not expected to be offered in the near future. However, they still count toward the major or minor in political science. You should always check with a department advisor if you have a question about a course that is not listed here.

A few courses fit intellectually into two different fields. They can be used to satisfy only one field requirement, however.

Required Course

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 202W Argument in Political Science

Techniques of Analysis

Techniques of Analysis, sometimes called political methodology, refers to a set of commonly used quantitative methods to analyze real-world data that can help us answer political questions. We consider it essential that students develop an understanding of the scientific method, master the role of deductive and inductive logic in answering research questions, and learn basic statistical techniques to summarize and analyze data. These sorts of skills will serve students well, regardless of their ultimate choice of career. For example, lobbyists, campaign fund raisers, lawyers, politicians, employees of government agencies, and academic political scientists all need to be able to read and easily comprehend reports in which numerical summaries of data (statistics) are used as evidence to support the claims of one group or another. The ability to determine whether these data are being used appropriately is invaluable in many careers that our students choose. In addition, in many of these careers, a person finds it necessary to do his or her own quantitative research to find answers to questions related to politics. For these reasons, courses that give particular emphasis to quantitative techniques of analysis are an important component of an education in political science. While there are a number of alternatives from which you may choose to fulfill the field requirement in techniques of analysis, the courses offered by political science faculty in the department teach techniques by asking and answering important substantive questions about politics. These courses are, therefore, particularly well suited to students majoring in political science.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

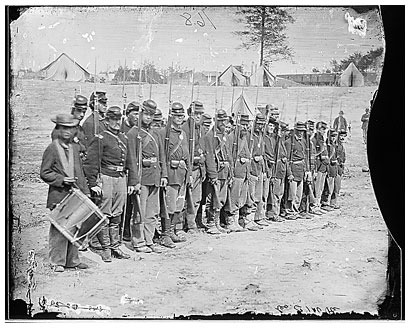

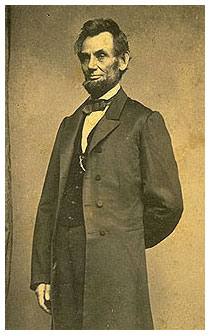

American Politics

American Politics is both a primary laboratory for developing an understanding of politics generally and a means for acquiring an understanding of our contemporary political system. As one of the largest areas of study in political science (and the largest in our department), the study of American politics is extremely varied in terms of subject matter, level of government examined, and analytic and methodological approach. As for subject matter, courses in American politics typically explore the attitudes or behavior of the mass public, or some combination of the two-for example, in terms of public opinion, voting choices, or decisions about political participation-or the actions of elites in formal political institutions (such as courts, legislatures, bureaucracies, and executive offices such as the presidency) and in non-governmental organizations (interest groups). The focus of analysis varies from localities (cities or counties), to states, to the national level-as well as to the relationship between these different levels of government. The analytic approach taken to answer questions is diverse, as focus can shift from historical examples, to data amenable to statistical analysis, to in-depth interviews with political elites, to mathematical models of political processes. Courses in American politics reflect this diversity, and you will find a wide range of alternatives from which to choose.

American Politics is both a primary laboratory for developing an understanding of politics generally and a means for acquiring an understanding of our contemporary political system. As one of the largest areas of study in political science (and the largest in our department), the study of American politics is extremely varied in terms of subject matter, level of government examined, and analytic and methodological approach. As for subject matter, courses in American politics typically explore the attitudes or behavior of the mass public, or some combination of the two-for example, in terms of public opinion, voting choices, or decisions about political participation-or the actions of elites in formal political institutions (such as courts, legislatures, bureaucracies, and executive offices such as the presidency) and in non-governmental organizations (interest groups). The focus of analysis varies from localities (cities or counties), to states, to the national level-as well as to the relationship between these different levels of government. The analytic approach taken to answer questions is diverse, as focus can shift from historical examples, to data amenable to statistical analysis, to in-depth interviews with political elites, to mathematical models of political processes. Courses in American politics reflect this diversity, and you will find a wide range of alternatives from which to choose.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 103 Great Debates in American Democracy

- PSCI 105 Introduction to U.S. Politics

- PSCI 121 Democracy in America

- PSCI 124 Race and Politics in American History

- PSCI 194 Rochester Politics and Places

- PSCI 209 Interest Groups in America

- PSCI 210 Development of the American Party System

- PSCI 211 Conspiracy Theories in American Politics

- PSCI 212 The United States Supreme Court: The Constitution at a Crossroads

- PSCI 213 The U.S. Congress

- PSCI 214 Political Participation

- PSCI 214 Empirical Controversies in American Politics

- PSCI 215 American Elections

- PSCI 216 Legislative Politics

- PSCI 217 Politics and the Mass Media

- PSCI 218W Emergence of the Modern Congress

- PSCI 219 Congress as an Institution

- PSCI 220 Social Movements in the United States

- PSCI 222 U.S. Presidency

- PSCI 223 Constitutional Structure and Rights

- PSCI 224 African-American Politics (through Spring 2026 only)

- PSCI 225 Race and Political Representation (through Fall 2024 only)

- PSCI 226 Black Political Leadership

- PSCI 226W Act Locally? Local Government in the U.S.

- PSCI 227 Designing American Democracy

- PSCI 228 Race and Ethnicity in American Politics

- PSCI 231 Money in Politics

- PSCI 232 Controversies in Public Policy

- PSCI 232 Disagreement in a Democratic Society

- PSCI 234 Law and Politics in the U.S.

- PSCI 234W The Past and Future of Our Financial System

- PSCI 235 Organizational Behavior

- PSCI 235W The Political Economy of U.S. Food Policy

- PSCI 237 U.S. Policymaking Processes

- PSCI 238 Business and Politics

- PSCI 239K The Nature of Entrepreneurship

- PSCI 241 Race, History and Urban Politics

- PSCI 243 Environmental Politics

- PSCI 244 Politics and Markets: Innovation and The Global Business Environment

- PSCI 245 Aging and Public Policy

- PSCI 247 Green Markets: Environmental Opportunities and Pitfalls

- PSCI 248 Discrimination

- PSCI 249 Sports and the American City

- PSCI/INTR 260 Democratic Erosion

- PSCI 280 Political Accountability

- PSCI 291 First Amendment and Religion

- PSCI 294 Political Economy of African-American Communities

- PSCI 310 Political Parties and Elections

- PSCI 316 Political Participation

- PSCI 318 Emergence of the Modern Congress

- PSCI 319 American Legislative Institutions

- PSCI 510 Political Parties and Elections

- PSCI 513 Interest Group Politics

- PSCI 516 Political Participation

- PSCI 518 Emergence of the Modern Congress

- PSCI 519 American Legislative Institutions

- PSCI 523 American Politics Field Seminar

- PSCI 525 Race and Political Representation

- PSCI 530 Race, History and Urban Politics

- PSCI 535 Bureaucratic Politics

- PSCI 536 Corporate Political Strategy

- PSCI 540 American Political Institutions

- PSCI 545 Judicial Politics

Comparative Politics

Comparative Politics employs a comparative perspective to study political institutions, political processes, political cultures, and policy outcomes in settings other than our own country. The comparative perspective stimulates us to develop general explanations about politics and test them by considering experiences in different contexts. The comparative approach to politics may take the form of explicit cross-national comparison of two or more countries, designed to answer general questions about important relationships in politics-the relationship between different sorts of constitutional arrangements (such as electoral rules and executive-legislative arrangements) and the accountability of governments to citizens, for example. The comparison may employ quantitative methods (such as statistical analysis or mathematical modeling) or may be qualitative. It may restrict itself to several countries that are considered to be similar in some way or may be very wide-ranging. Alternatively, the comparative approach may focus on the politics of a single country. What makes such study comparative is the perspective adopted, which acknowledges and explores politics in a single country as one piece in a larger framework. The larger framework is the effort in the field of comparative politics to understand what is exceptional and what is general about politics in any context including our own. Courses in comparative politics exhibit the diversity described above, in terms of scope of comparison, regional focus, and thematic content.

Comparative Politics employs a comparative perspective to study political institutions, political processes, political cultures, and policy outcomes in settings other than our own country. The comparative perspective stimulates us to develop general explanations about politics and test them by considering experiences in different contexts. The comparative approach to politics may take the form of explicit cross-national comparison of two or more countries, designed to answer general questions about important relationships in politics-the relationship between different sorts of constitutional arrangements (such as electoral rules and executive-legislative arrangements) and the accountability of governments to citizens, for example. The comparison may employ quantitative methods (such as statistical analysis or mathematical modeling) or may be qualitative. It may restrict itself to several countries that are considered to be similar in some way or may be very wide-ranging. Alternatively, the comparative approach may focus on the politics of a single country. What makes such study comparative is the perspective adopted, which acknowledges and explores politics in a single country as one piece in a larger framework. The larger framework is the effort in the field of comparative politics to understand what is exceptional and what is general about politics in any context including our own. Courses in comparative politics exhibit the diversity described above, in terms of scope of comparison, regional focus, and thematic content.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI/INTR 101 Introduction to Comparative Politics

- PSCI/INTR 250 Comparative Democratic Representation

- PSCI/INTR 250 Conflict in Democracies

- PSCI/INTR 251 Politics of Authoritarian Regimes

- PSCI/INTR 251 Political Economy of Development

- PSCI/INTR 252 Ethnic Politics and Ethnic Conflict

- PSCI/INTR 253 Comparative Political Parties

- PSCI/INTR 255 Poverty and Development

- PSCI/INTR 256 Theories of Comparative Politics

- PSCI/INTR 257 The Origins of the Modern World

- PSCI/INTR 258 Democratic Regimes

- PSCI/INTR 259 Order, Violence, and the State

- PSCI/INTR 260 Democratic Erosion

- PSCI/INTR 260 Contemporary African Politics

- PSCI/INTR 261 Latin American Politics

- PSCI/INTR 262 Elections in Developing Countries

- PSCI/INTR 262 Globalization Past and Present

- PSCI/INTR 263 Comparative Law and Courts

- PSCI/INTR 264 Comparative Political Institutions

- PSCI/INTR 265 Civil War and the International System

- PSCI/INTR 266 The Politics of India and Pakistan

- PSCI/INTR 267 Identity, Ethnicity and Nationalism

- PSCI/INTR 268 Economics and Elections

- PSCI/INTR 271 Territory and Group Conflict

- PSCI/INTR 271 Russia and Eastern Europe: Politics and International Relations

- PSCI/INTR 274 International Political Economy

- PSCI/INTR 276 The Politics of Insurgency

- PSCI/INTR 350 Comparative Politics Field Seminar

- PSCI/INTR 351 Western European Politics

- PSCI/INTR 355 Democratic Political Processes

- PSCI/INTR 356 Political Economy of Reform

- PSCI/INTR 364 Comparative Political Economy

- PSCI/INTR 373 Territory and Group Conflict

- PSCI 465 Civil War and the International System

- PSCI 471 Russia and Eastern Europe: Politics and International Relations

- PSCI 503 Formal Modeling in Comparative Politics

- PSCI 550 Comparative Politics Field Seminar

- PSCI 551 Western European Politics

- PSCI 553 Ethnic Politics

- PSCI 555 Democratic Political Processes

- PSCI 556 Political Economy of Reform

- PSCI 558 Comparative Parties and Elections

- PSCI 561 Latin American Politics

- PSCI 562 Empirical Research Practicum

- PSCI 563 Causal Inference: Applications and Interpretation

- PSCI 564 Comparative Political Economy

- PSCI 565 Political Economy of Development

- PSCI 569 State Formation

- PSCI 570 Civil Order and Civil Violence

- PSCI 573 Territory and Group Conflict

- PSCI 580 Models of Non-Democratic Politics

International Relations

International Relations is the study of conflict and cooperation in the interstate system and the world economy. The players are diverse: nation-states, international organizations, sub-national actors (such as unions and firms), and transnational actors (such as the Catholic Church). Major questions include the origins of war and peace, the effects of a global economy on domestic politics, and the causes of international integration. For example, it is an empirical fact that democracies are less likely to fight each other than are non-democracies. Why is this the case? There is a panoply of competing explanations, many of which are mutually exclusive. The task for the student of international politics is to find general explanations for such observations: for example, wars may be caused by strategic bluffing during crises; if democratic politics makes it more difficult to hide true objectives from opponents, unintended wars may be avoided. How could this hypothesis be tested? We could carefully compare cases to determine whether this is in fact what distinguished democratic from non-democratic belligerents, or we could use statistical analysis to determine whether democracies are in fact less likely than non-democracies to bluff in a variety of contexts. Courses in international politics provide students with the historical background necessary to understand current events and train them to study international phenomena with the tools of social science. Courses offered in the department range in content and approach and include historical surveys, courses on particular international conflicts or the foreign relations of particular countries, and courses on theoretical approaches to international relations.

International Relations is the study of conflict and cooperation in the interstate system and the world economy. The players are diverse: nation-states, international organizations, sub-national actors (such as unions and firms), and transnational actors (such as the Catholic Church). Major questions include the origins of war and peace, the effects of a global economy on domestic politics, and the causes of international integration. For example, it is an empirical fact that democracies are less likely to fight each other than are non-democracies. Why is this the case? There is a panoply of competing explanations, many of which are mutually exclusive. The task for the student of international politics is to find general explanations for such observations: for example, wars may be caused by strategic bluffing during crises; if democratic politics makes it more difficult to hide true objectives from opponents, unintended wars may be avoided. How could this hypothesis be tested? We could carefully compare cases to determine whether this is in fact what distinguished democratic from non-democratic belligerents, or we could use statistical analysis to determine whether democracies are in fact less likely than non-democracies to bluff in a variety of contexts. Courses in international politics provide students with the historical background necessary to understand current events and train them to study international phenomena with the tools of social science. Courses offered in the department range in content and approach and include historical surveys, courses on particular international conflicts or the foreign relations of particular countries, and courses on theoretical approaches to international relations.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI/INTR 102 Introduction to International Political Economy

- PSCI/INTR 106 Introduction to International Relations

- PSCI/INTR 251 Political Economy of Development

- PSCI/INTR 252 Ethnic Politics and Ethnic Conflict

- PSCI/INTR 255 Poverty and Development

- PSCI/INTR 259 Order, Violence, and the State

- PSCI/INTR 262 Globalization Past and Present

- PSCI/INTR 265 Civil War and the International System

- PSCI/INTR 268 International Organization

- PSCI/INTR 270 Mechanisms of International Relations

- PSCI/INTR 271 Russia and Eastern Europe: Politics and International Relations

- PSCI/INTR 271 Territory and Group Conflict

- PSCI/INTR 272 Theories of International Relations

- PSCI/INTR 273 The Politics of Terrorism

- PSCI/INTR 274 International Political Economy

- PSCI/INTR 276 The Politics of Insurgency

- PSCI/INTR 278 Foundations of Modern International Politics

- PSCI/INTR 279 War and the Nation State

- PSCI/INTR 356 Political Economy of Reform

- PSCI/INTR 364 Comparative Political Economy

- PSCI/INTR 372 International Politics Field Seminar

- PSCI/INTR 373 Territory and Group Conflict

- PSCI/INTR 374 International Political Economy

- PSCI 465 Civil War and the International System

- PSCI 471 Russia and Eastern Europe: Politics and International Relations

- PSCI 479 War and the Nation State

- PSCI 553 Ethnic Politics

- PSCI 556 Political Economy of Reform

- PSCI 564 Comparative Political Economy

- PSCI 568 International Organization

- PSCI 569 State Formation

- PSCI 570 Civil Order and Civil Violence

- PSCI 571 Quantitative Approaches to International Politics

- PSCI 572 International Politics Field Seminar (obsolete)

- PSCI 573 Territory and Group Conflict

- PSCI 574 International Political Economy

- PSCI 576 Modeling International Conflict

- PSCI 577 Theories of Conflict

- PSCI 578 International Conflict: Theory and History

- PSCI 579 Politics of International Finance

Positive Theory

Positive Theory is the study of political processes by using logical or mathematical reasoning to deduce conclusions about political behavior and outcomes from precise initial assumptions about political actors' preferences, information, and opportunities. You will encounter three important examples of positive theory in many political science courses-not only courses in the positive theory field. First, there is a well developed positive theory of voting and elections. This theory is used to analyze the strategies candidates use to gain victory, based on voters' preferences about the results of government policies. The same theory is often used to understand how legislators vote on bills. Second, the positive theory of collective action is often used to understand the problems involved in getting people with different individual goals to work together toward a common goal. Third, the positive theory of social choice is concerned with problems inherent in creating democratic processes for influencing government policies when public opinion about those policies is mixed. Courses in positive theory focus on how this sort of formal reasoning works, no matter what the particular political situation, and teach you how to use positive theory to draw extremely important, general lessons about politics across a wide variety of situations.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 107 Introduction to Positive Political Theory

- PSCI/INTR 108 Introduction to Political Economy

- PSCI/INTR 272 Theories of International Relations

- PSCI 280 Political Accountability

- PSCI 281 Formal Models in Political Science

- PSCI 285 Strategy and Politics

- PSCI 286 Political Economy

- PSCI 287 Theories of Political Economy

- PSCI 288 Game Theory

- PSCI/INTR 374 International Political Economy

- PSCI 407 Mathematical Modeling

- PSCI 408 Positive Political Theory

- PSCI 487 Theories of Political Economy

- PSCI 502 Political and Economic Networks

- PSCI 503 Formal Modeling in Comparative Politics

- PSCI 574 International Political Economy

- PSCI 575 Topics in Political Economy

- PSCI 576 Modeling International Conflict

- PSCI 580 Models of Non-Democratic Politics

- PSCI 584 Game Theory

- PSCI 585 Dynamic Models: Structure, Computation and Estimation

- PSCI 586 Voting and Elections

- PSCI 588 Bargaining Theory and Applications

- PSCI 589 Advanced Formal Methods in Political Economy

Political Philosophy

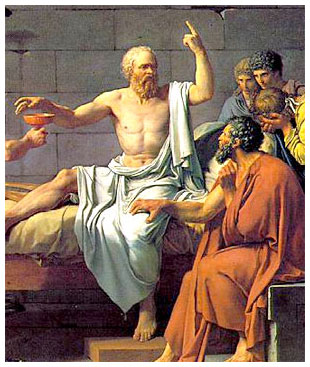

Political Philosophy addresses basic conceptual and normative questions and probes the intuitive, seemingly obvious answers we give to them. What are rights and why do we value them? How do we conceive of freedom and what limits, if any, may government legitimately impose on individual freedom? What is power, how does it operate in politics, and when is the exercise of power justified? Politicians and ordinary citizens regularly answer such questions, and they regularly do so in very different ways. The answers they offer, although seemingly common sensical, often raise complex, unforseen philosophical problems. Political philosophy deals with problems that arise when politicians and ordinary citizens attempt to specify and justify basic political commitments. The approach of political philosophy can be historical or analytical, and it is usually both. Historically, it attempts to learn from how great writers of the past address foundational questions. It asks, for example, how Socrates, Antigone, Henry David Thoreau, or Martin Luther King, Jr. justified civil disobedience, and how and why their respective justifications differ. Analytically, it explores the structure of political concepts. For example, it asks not only what rights are, but more precisely whether rights protect the choices or the interests of actors, and whether we can coherently ascribe rights to groups or only to individuals. Courses in political philosophy engage, to varying degrees, in both historical and analytical inquiry. In this way, they prompt students to engage with the fundamental issues of politics.

Political Philosophy addresses basic conceptual and normative questions and probes the intuitive, seemingly obvious answers we give to them. What are rights and why do we value them? How do we conceive of freedom and what limits, if any, may government legitimately impose on individual freedom? What is power, how does it operate in politics, and when is the exercise of power justified? Politicians and ordinary citizens regularly answer such questions, and they regularly do so in very different ways. The answers they offer, although seemingly common sensical, often raise complex, unforseen philosophical problems. Political philosophy deals with problems that arise when politicians and ordinary citizens attempt to specify and justify basic political commitments. The approach of political philosophy can be historical or analytical, and it is usually both. Historically, it attempts to learn from how great writers of the past address foundational questions. It asks, for example, how Socrates, Antigone, Henry David Thoreau, or Martin Luther King, Jr. justified civil disobedience, and how and why their respective justifications differ. Analytically, it explores the structure of political concepts. For example, it asks not only what rights are, but more precisely whether rights protect the choices or the interests of actors, and whether we can coherently ascribe rights to groups or only to individuals. Courses in political philosophy engage, to varying degrees, in both historical and analytical inquiry. In this way, they prompt students to engage with the fundamental issues of politics.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 104 Introduction to Political Philosophy

- PSCI/INTR 108 Introduction to Political Economy

- PSCI 121 Democracy in America

- PSCI 221 Philosophical Foundations of the American Revolution

- PSCI 282 Art and Politics

- PSCI 283 Contemporary Political Theory

- PSCI 284 Democratic Theory

- PSCI 286 Political Economy

- PSCI 287 Theories of Political Economy

- PSCI 291 First Amendment and Religion

- PSCI 292 Ethics in Markets and In Public Policy

- PSCI 292 Rousseau to Revolution

- PSCI 293 The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass

- PSCI 294 Political Economy of African-American Communities

- PSCI 380 Scope of Political Science

- PSCI 383 Culture and Politics

Introductory Courses

Note: Introductory courses count toward their respective fields.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI/INTR 101 Introduction to Comparative Politics

- PSCI/INTR 102 Introduction to International Political Economy

- PSCI 103 Great Debates in American Democracy

- PSCI 104 Introduction to Political Philosophy

- PSCI 105 Introduction to U.S. Politics

- PSCI/INTR 106 Introduction to International Relations

- PSCI 107 Introduction to Positive Political Theory

- PSCI/INTR 108 Introduction to Political Economy

- PSCI 117 Introduction to American Government

- PSCI 121 Democracy in America

- PSCI 124 Race and Politics in American History

- PSCI 151 Political Economy of Developing Countries

- PSCI 167M Democracy: Past and Present

Individual Research

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 208 Undergraduate Research Seminar

- PSCI/INTR 389W Senior Honors Seminar

- PSCI 390 Supervised Teaching

- PSCI 391 Directed Reading/Independent Study

- PSCI 392 Practicum

- PSCI/INTR 393W Senior Honors Project

Internship

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 394 Internships in Politics, Law, and Civic Life

- PSCI/INTR 394C Washington Semester Internship

- PSCI 399 Washington Semester

Associated Courses

Associated Courses are typically taught by faculty with a long-standing association with the department or scholars invited to the department for research and teaching. They include professors with doctorates in disciplines other than political science as well as professors with significant practical experience in law, politics, and public policy.

Only active courses are shown below. To see the archived courses also, click here.

- PSCI 115 Intro to Comparative Politics

- PSCI 117 Introduction to American Government

- PSCI 121 Sustainable Food Systems

- PSCI 140 Politics & The Mass Media

- PSCI 150 Intro to American Politics

- PSCI 151 Political Economy of Developing Countries

- PSCI 152 Politics in Developing Nations

- PSCI 160 Campaigns & Elections: A Global Perspective

- PSCI 161 Introduction to International Politics

- PSCI 162 Business and Foreign Policy

- PSCI 164 Politics of Authoritarian Regimes

- PSCI 167 Politics of the Middle East

- PSCI 167M Democracy: Past and Present

- PSCI 169 Politics of New Europe

- INTR 200 Politics of Authoritarian Regimes

- INTR 201 Comparative Legislatures and Executives

- INTR 202 India, Pakistan, and the Politics of South Asia

- PSCI 204 Research Design

- INTR 204 Dictatorship and Democracy

- INTR 205 Global Sustainable Development

- INTR 210 Russian Politics

- INTR 211 Political Economy of Africa

- INTR 212 Democratization in Non-Western Societies

- INTR 213 Political and Economic Development in Post-Colonial Societies

- INTR 214 Political Violence in Comparative Perspective

- INTR 215 Corruption and Good Governance

- INTR 215 Populism in 21st Century Politics

- INTR 216 Political Economy of Post-Communism

- PSCI/INTR 217 How Countries Become Rich

- INTR 218 China & Asia: Politics and Economics

- INTR 219 Democracy in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico

- INTR 220 Non-State Actors in World Politics

- INTR 220 Elections, Parties and Coalitions in Comparative Perspective

- INTR 221 International Politics of Development

- INTR 221 European Nationalism

- INTR 222 Preventive Wars

- INTR 222 Politics of New Europe

- INTR 223 Opposition in an Authoritarian State: Poland, 1945-1989

- PSCI 224 Incarceration Nation (through Spring 2026 only)

- INTR 224 Domestic Politics and International Relations

- PSCI 225 Cultural Politics of Prison Towns (through Fall 2024 only)

- INTR 225 Politics & Policymaking in the Developing World

- INTR 226 America's 21st Century Wars

- PSCI 227 The Black Arts Movement

- INTR 227 Peace and War

- INTR 228 International Security (through Fall 2025 only)

- PSCI 229 The Civil Rights Era and Its Legacy

- PSCI 229 Environmental Health Policy

- INTR 229 Terrorism

- INTR 229 International Political Economy

- PSCI 230 Public Health Law and Policy

- INTR 230 American Foreign Policy

- INTR 231 Counterinsurgency in Theory and Practice

- INTR 231 Cold War

- PSCI 231W Maternal Child Health Policy and Advocacy

- INTR 232 Political Economy of Europe

- PSCI 233 Community Development and Political Leadership

- INTR 233 Internal Conflict and International Intervention

- PSCI 233W Innovation in Public Service

- INTR 234 Comparative Authoritarianism

- INTR 235 Elections under Democracy and Dictatorship

- PSCI 236 Health Care and the Law

- INTR 236 Contentious Politics and Social Movements

- INTR 237 Gender and Development

- INTR 238 Political Economy of International Migration

- PSCI/INTR 239 International Environmental Law

- INTR 239 Women, Men, Gender and Development

- PSCI 240 Criminal Procedure and Constitutional Principles

- INTR 240 Human Rights, Minorities and Migration in Europe

- INTR 241 Polish Foreign Policy After Communism, 1989-2019

- PSCI 242 Courts, Communities, and Injustice in America

- PSCI 242 Research Practicum in Criminal Justice Reform

- PSCI 246 Women in Politics

- PSCI 246 Environmental Law and Policy

- INTR 246 Religious Nationalism (through Spring 2026 only)

- INTR 247 Zionism and Its Discontents

- PSCI/INTR 248 Politics of the Middle East

- INTR 248 The Arab-Israeli Conflict

- PSCI 249 Environmental Policy in Action

- INTR 249 Israel/Palestine (through Fall 2025 only)

- PSCI/INTR 254 The U.S. in the Middle East

- PSCI/INTR 257 Poland in the New Europe

- PSCI/INTR 260 The Cold War: Europe between the US and the USSR

- PSCI/INTR 266 Politics of the European Union

- PSCI/INTR 269 Russian Politics

- PSCI/INTR 273 Political Economy of East Asia

- PSCI/INTR 275 American Foreign Policy

- PSCI/INTR 277 International Security

- PSCI/INTR 278 War and Political Violence

- INTR 280 Communism and Democracy in Eastern Europe

- INTR 280 The Politics and Economy of China

- INTR 281 Business and Politics in Eastern and Central Europe

- INTR 282 Eastern Europe: Philosophy and Reform

- INTR 283 Post-Soviet Politics: Democracy, Authoritarianism, and Elections

- INTR 283 Politics in the European Union

- PSCI 285 Legal Reasoning and Argument

- INTR 286 Political Economy of Developing Countries

- PSCI/INTR 289 The Role of the State in Global Historical Perspective

- PSCI 290 Unequal Development and State Policy: Brazil, the U.S., and Nigeria

- PSCI 304 Urban Crime and Justice

- PSCI 305 Poverty and Mental Health

- PSCI 385 Legal Reasoning & Argument