Tsoifest Schedule

Thursday 9/22, May Room (WILCO)

7 p.m.—Film Screening

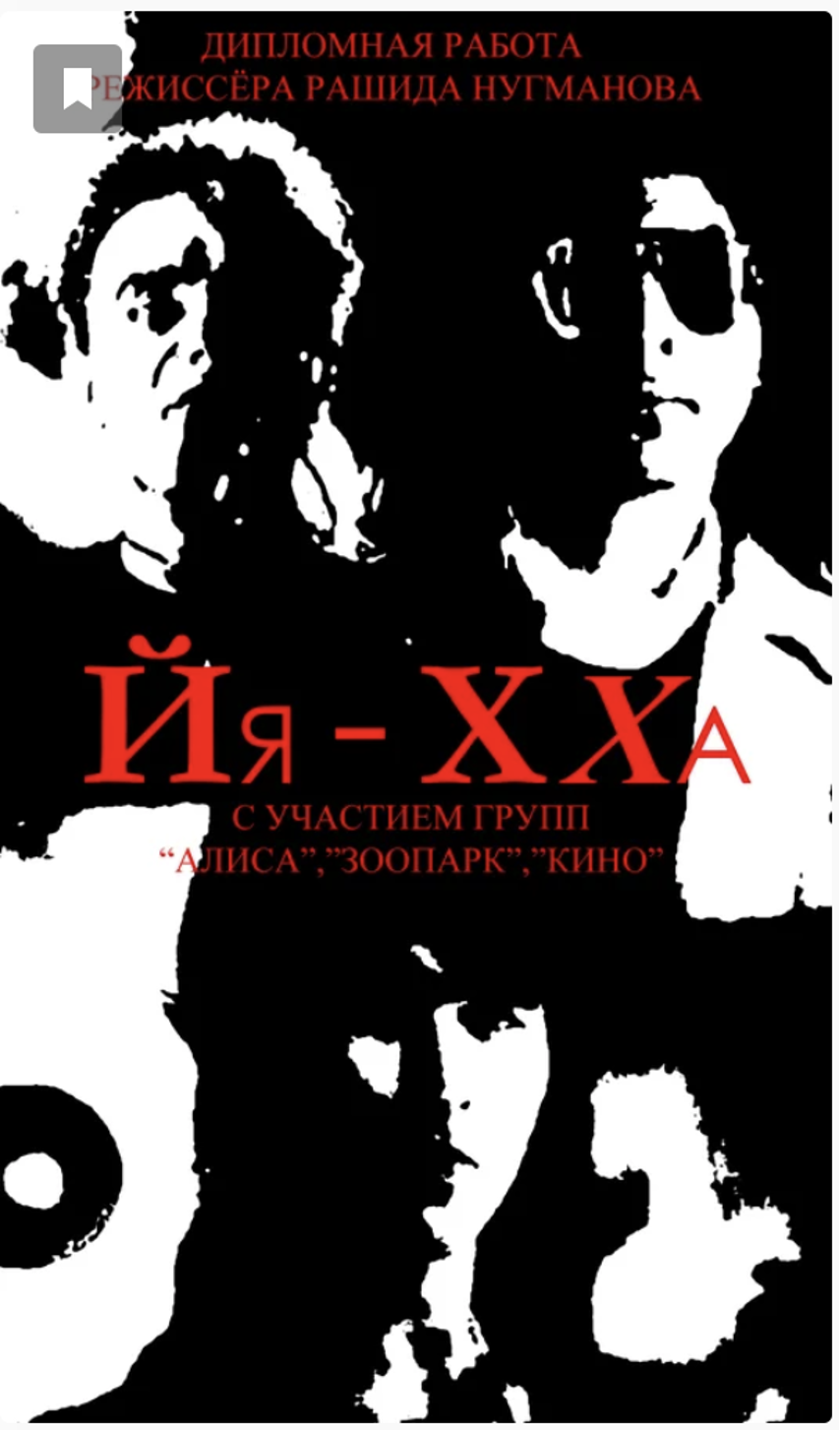

Йя-хха (Yahha, 1986, 35 min) followed by Q&A with director Rachid Nougmanov.

Description: Yahha (1986) directed by Rachid Nougmanov is a whimsical, atmospheric look into a day in the life of the underground rock music scene in Gorbachev-era Leningrad. The documentary follows a group of young music fans on a kaleidoscopic journey that includes a performance in a boiler room, a raucous punk wedding, and irreverent street banter, all the while capturing the freewheeling spirit of a budding youth subculture on the cusp of a seismic sociopolitical shift. The film features some of the most prominent Perestroika-era rock musicians, including Viktor Tsoi, Konstantin Kinchev, and Mike Naumenko. (In Russian with English subtitles).

8 p.m.—Musical Performance

Kino Proby

Description: In the fall of 2004, Kino Proby was born at the Bottomz Up! bar over a pitcher of PBR. As undergrads at the University of Rochester, Viktors I & II became fans of the Soviet rock group KINO while studying abroad in St. Petersburg in the fall of 2000. Returning to their alma mater for a Tosifest reunion, the Viktors will rock the May Room in Wilson Commons like we’re “Back in the USSR”!

Friday 9/23, Gowen Room (WILCO)

Noon—Keynote

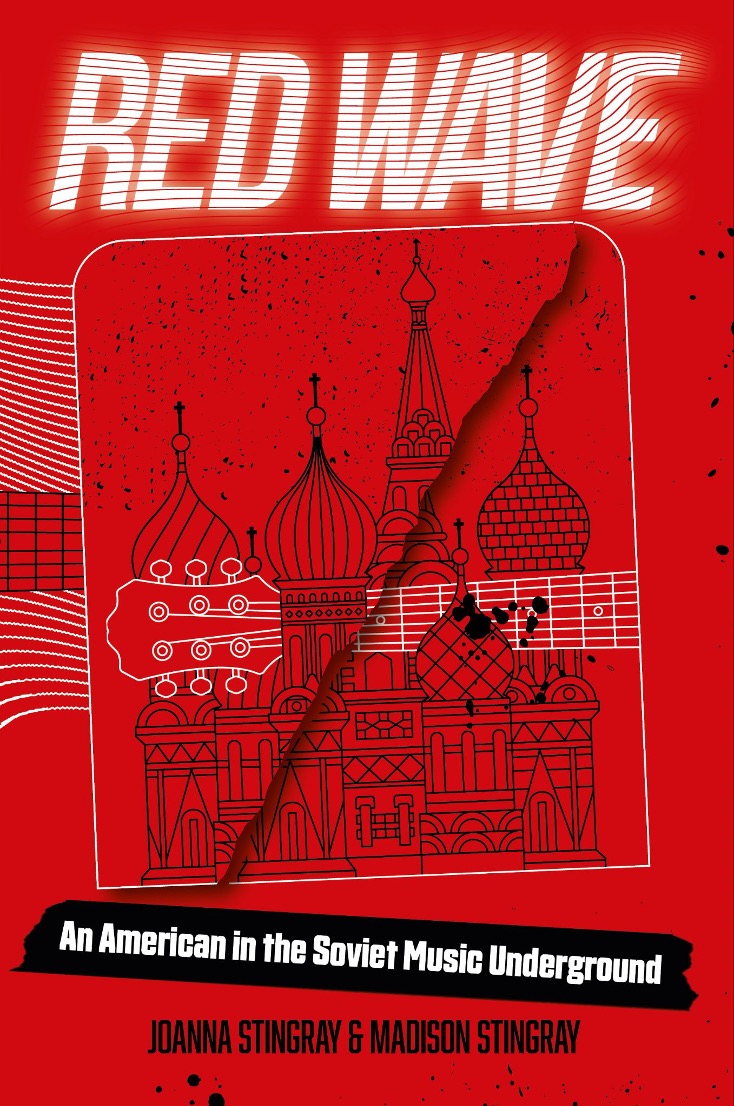

Joanna Stingray “Red Wave: An American in the Soviet Music Underground”

Description: In her keynote address, Joanna Stingray will introduce Tsoifest’s audience to the legendary musicians of Soviet rock through an account of her improbable Cold War heroics as a young New Wave musician who, in 1985, produced Red Wave: 4 Underground Bands from the USSR with music by her new friends that she had smuggled to the West. This is her incredible testimony of youthful fortitude and rebellion, her love story, and proof of the power of music and youth culture over stagnancy and oppression.

Mode: Hybrid, in-person and Zoom webinar

2 p.m.—Roundtable Discussion

Tsoi Today

Speakers: Joanna Stingray, Rachid Nougmanov, with special virtual guest Alexander Tsoi (Viktor Tsoi’s son) joining remotely from St. Petersburg. Moderated by Rita Safariants and Gabrielle Cornish.

Mode: Hybrid, in-person and Zoom webinar

4 p.m.—Film Screening

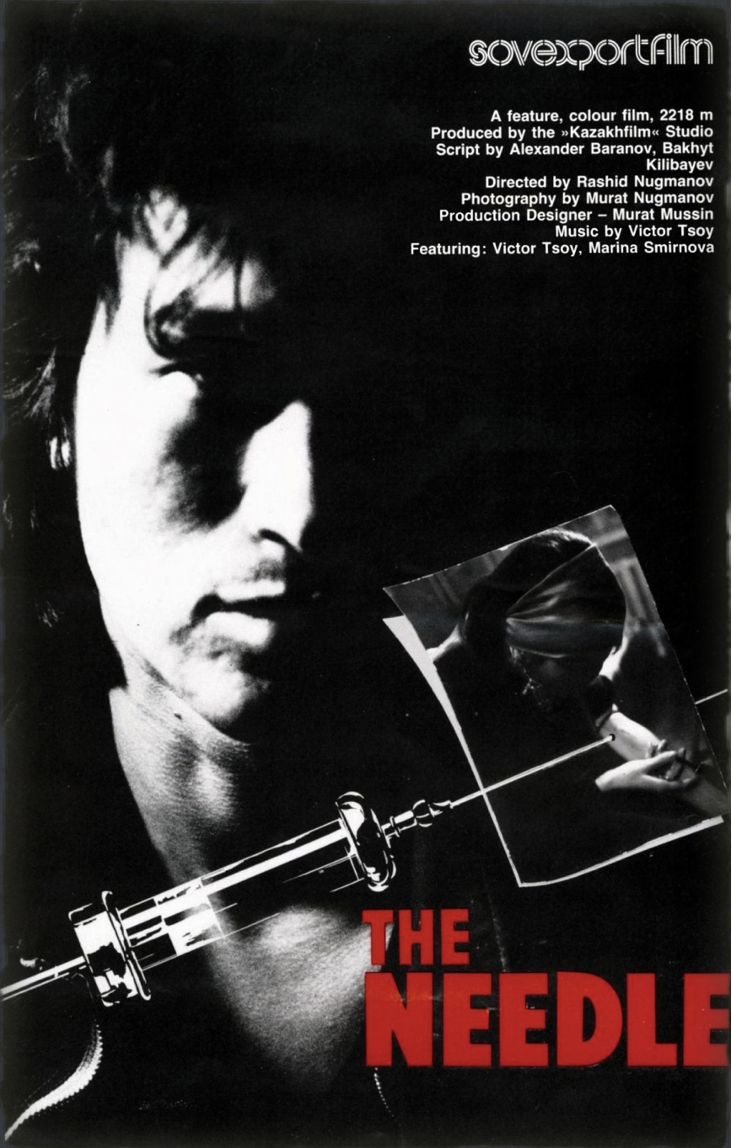

The Needle (1988, 81 min.) followed by Q&A with director Rachid Nougmanov

Description: As the founding text of the Kazakh New Wave, The Needle directed by Rachid Nougmanov established Viktor Tsoi as the ultimate rock icon of the Perestroika era. Tsoi stars in the film’s leading role as Moro, a former gangster, who returns to his native Alma-Aty to collect a long-standing debt. While waiting out an unexpected delay, he visits his former girlfriend Dina, and discovers she has become a morphine addict. He decides to help her kick the habit and to fight the local drug mafia responsible for her condition. Kino’s post-punk soundtrack serves as the sonic complement to the film’s experimental visual style.

(In Russian with English subtitles)

Saturday 9/24, Gowen Room (WILCO)

11 a.m.—Panel One

Tsoi’s Cultural Legacies: Past, Present, and Future

Paper 1: “Tsoi’s mentors? BG, Maik and Vit’ka, and the question of influence”

Polly McMichael (University of Nottingham, England)

Abstract: Accounts of Viktor Tsoi’s emergence in the Leningrad rock scene at the start of the 1980s foreground formative relationships with two older, already established rock performers, Boris Grebenshchikov and Mikhail ‘Maik’ Naumenko, both of whom were early champions of Tsoi’s music. The legendary first meeting of Tsoi and Grebenshchikov that took place on a suburban train taking them home from Peterhof offers itself up to interpretations of Tsoi’s relationship to Grebenshchikov as one of creative apprenticeship, the pupil stunning his teacher with a display of god-bestowed talent. In Kirill Serebrennikov’s film Leto, Tsoi is similarly imagined as preternaturally gifted youngster, fast outgrowing his mentor’s influence. This paper seeks to take apart these myths and investigate Tsoi’s relationships with Grebenshchikov and Naumenko from the point of view of the mutual, two-way processes of inspiration and influence taking place. A key area of focus will be the way in which all three author-performers dealt with the urgency and contemporaneity they perceived in music and their responses to subgenres and trends. For instance, as Tsoi and his bandmates in Kino worked on a distinctive sound and image incorporating aspects of New Wave, Grebenshchikov was engaged in his own forays into New Wave aesthetics. Tsoi could not have emerged as he did as the rock star par excellence of the perestroika era without the complex dynamics of the established and rapidly evolving Leningrad scene, but he also changed the course of this scene, influencing the creative decisions made by his supposed elders. This paper aims to shed light both on Leningrad rock’s ‘generational’ nature (cf Steinholt 2004), and on what this meant for three intersecting creative careers.

Paper 2: “‘Fast-ripening fruits’: The Kino generation’s templates of destruction”

Joy Neumeyer

Abstract: While some of late socialism’s cult figures burned out slowly in middle age, the heroes of the perestroika generation were (in the words of Viktor Tsoi) “fast-ripening fruits.” Like many of their peers, Alexander Bashlachev and Tsoi were less interested in Moscow and the bards than in Leningrad and The Doors. But they still came of age in Vladimir Vysotskii’s shadow—especially Bashlachev, who wrote songs reminiscent of Vysotskii’s sardonic odes to martyrdom (such as “The Jester’s Funeral” and “On the Life of Poets”). Vysotskii’s style of morbidity had captured the apparently unchanging here-and-now of the Brezhnev era. The Kino generation, however, demanded a different future that seemed to come fatally quickly. After proclaiming that death was coming soon in “By Screws” (Ot vinta), Bashlachev jumped out of a window at age 27. Tsoi, Bashlachev’s friend and chief mourner, placed his guitar on the coffin before dying in a car crash two years later. Alexei Uchitel’s documentary The Last Hero (1992) shows mourning teenagers who have taken up residence in the Leningrad cemetery where he is buried; one of them says that her only dream is to lie near Tsoi’s grave. This paper will analyze Bashlachev and Tsoi’s performances of destruction and the cultural reception of their deaths in the context of their late socialist antecedents and the Soviet Union’s demise.

Paper 3: “Raising the Dead: Viktor Tsoi’s Post-Soviet Cinematic Legacy”

Rita Safariants (University of Rochester)

Abstract: In the decade preceding the collapse of the USSR, rock music became a galvanizing force for change and an enduring cultural commodity for the last Soviet generation. In the wake of Gorbachev’s reforms, the traditionally western musical genre quickly infiltrated the highly regimented Soviet film industry, with rock music themed films becoming symbols of the Perestroika era while engineering the cult of Soviet rock celebrity. Curiously, the turn of the new millennium saw a resurgence in references to rock music and deceased rock musicians in Russian cinema. Established directors invested their time into film projects that celebrated and paid homage to the late-Soviet rock star. This paper will consider two such films: Kirill Serebrennikov’s 2018 audience hit Summer and Alexey Uchitel’s 2020 “posthumous biopic” Tsoy, as two ideologically disparate examples of the enduring significance of Soviet rock music under the sociopolitical conditions of Putin’s Russia, and will frame the functions that nostalgia, historical verisimilitude, and intertextual dialogue serve in contemporary cinematic discourse.

Paper 4: “Viktor Tsoi’s “Kukushka”: Ideological Transformations and Russian Geopolitics in Post-Soviet Popular Music”

Shaun Hillen (Sam Houston State University)

Abstract: In May 2018, a ten-year-old Russian girl wearing the latest in children’s military couture belted out a pop cover of Viktor Tsoi’s “Kukushka/cuckoo” (released posthumously in 1990) before an audience of construction workers gathered for the opening of a strategic bridge linking Russia to Crimea. As she sang, television audiences witnessed an infamous, nationalistic biker gang leading a symbolic charge over the bridge into the Ukrainian territory controversially annexed by Russia in 2014. The combination of sound and patriotic imagery underscored conquest as the collective destiny of the Russian people. Yet this rousing pageantry stood in stark contrast to the struggle with creative doubts laid bare in the late-Soviet original by the understated Viktor Tsoi (1962–90), the famous lead singer of the seminal Leningrad rock group Kino. This paper traces the transformation of “Kukushka” across a number of recent cover versions by such female artists as Olga Kormukhina, Polina Gagarina, and Yaroslava Degtyareva. It draws from an eclectic ethnographic data set collected from the underexplored comment sections of Russian social media as well as from informants within Russia and across the post-Soviet diaspora. Transformed through generic and stylistic shifts—achieved by new performance venues, changes in performance practice, the addition of conspicuous costuming, and the incorporation into state-funded cinema—these latest iterations more closely resemble the theatrical aesthetic of late-Soviet variety song, or estrada, than Tsoi and his band Kino’s brooding new wave rock. What emerges from the cover versions of “Kukushka” produced between 2012 and 2022, which predominantly appear in concerts or projects funded by the Russian Ministry of Culture, is arguably a new song, entirely divorced from Tsoi’s pacifist philosophy. “Kukushka” has become a militant anthem calling the nation to shed its wounded pride and defiantly take back what was ostensibly stolen from it after the breakup of the USSR. Gagarina’s performance at Moscow’s Luzhniki stadium in March of this year in support of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine represents the apex of this transformative phenomenon, further cementing the song’s associations with conquest. This paper contributes to musicological discourses concerning music’s relationship to power as well as its role in building (and rebuilding) often mythical national identities.

2:30 p.m.—Panel Two

Tsoi and His Musical Communities

Paper 1: “Sergey Kuryokhin and Soviet Rock”

Peter Schmelz (Arizona State University)

Abstract: In a 1987 interview published in Keyboard magazine, Sergey Kuryokhin said, “I like to have lots of guitars onstage; they create a much higher possibility of accidents.” Delivered in Kuryokhin's characteristic mode of flippant truth-telling, the quip illuminates his musical practice, socially, historically, and aesthetically. A sometime participant in such central Soviet rock bands as Akvarium and Alisa, Kuryokhin also formed his own ensemble, Pop-Mekhanika, which collided members from multiple groups, styles, and genres. Many of his performances with Pop-Mekhanika in the mid-to-late 1980s indeed featured batteries of guitars churning out noisy riffs in semi-unison. For all the unpredictability and variability of Pop-Mekhanika, these guitar walls formed an essential feature of the group’s sound and approach at the time. Among the guitarists were members of several Soviet rock bands, perhaps most notably Viktor Tsoi. This paper uses three key videos from 1985–87 to explore Kuryokhin’s collaborations with Soviet rock musicians, Tsoi foremost among them. The first video appeared in 1985 as part of a groundbreaking 12-part BBC documentary on the USSR called Comrades. The third episode in the series, “All that jazz,” focused on “unofficial” music, using Kuryokhin as a guide. Especially memorable is an ad hoc performance of Alisa’s song “Experimentator,” featuring, in addition to Konstantin Kinchev on vocals, Kuryokhin on synthesizer, Sasha Titov (of Akvarium and Kino) on bass, and Sergey Bugayev (Afrika) on percussion. Tsoi also appears in several Pop-Mekhanika segments in the documentary. Tsoi and Boris Grebenshchikov were next seen with Kuryokhin in a raucous performance film from 1986 called Dialogues (Dialogi), which also included saxophonist Vladimir Chekasin (of the Ganelin Trio) alongside other well-known musicians. Finally, Kuryokhin’s landmark appearance on the television show Musical Ring (Muzykal’nyi ring), recorded in April 1987, again highlighted Tsoi, in addition to Oleg Garkusha (from the group Auktsyon), Afrika, and many other familiar figures. These three audiovisual moments clarify Kuryokhin’s interactions (both accidental and intentional) with the Soviet rock scene. More broadly, they help clarify the musicking that defined this scene: the cross-generic, polystylistic experimentation at its core. As a result, these audiovisual examples further tell us about friendship, mediation, and popular music stardom during the last decade of the USSR.

Paper 2: “Mix, Cuts & Scratches: Tape Art and Postmodern Belonging on the Transit Riga–West Berlin”

Kevin Karnes (Emory University)

Abstract: In his cult-classic 1999 history of underground Soviet rock, Aleksandr Kushnir devoted two of his 100 chapters to a curious outfit, the Latvian band the Yellow Postmen. Outliers not only for singing in Latvian and identifying with Western bands like Talking Heads and the Police, the Yellow Postmen were remarkable for crafting music that could not possibly be recreated live. Applying intensively the techniques of cutting, splicing, looping, and overlaying massive piles of magnetic tape, the band approached the studio itself like a musical instrument, creating music that could only be realized via the medium, and could only be experienced in playback, never through performance on stage. In my presentation, I delve deeply into this phenomenon of “tape art” that laid the soundtrack for one particular Soviet subculture of the 1980s. I trace origins for many tape art projects in the unlikely visit of a West German DJ to Riga, where demonstrations of his “record art” (mixing, scratching, and cutting) and performances with such diverse outfits as Pop Mekhanika, Kino, and Hardijs Lediņš’s “Approximate Art Agency” inspired a wave of experimentation not with LPs but with magnetic tape, the most widely available technology for sound reproduction in the late USSR. In turn, these tape art experiments prompted a wave of imagining by Lediņš and others, who heard in these experiments with tape the possibility for a distinctly Latvian contribution to a global postmodern culture, in a moment when the Soviet regime still seemed to be eternal.

Paper 3: “Late Socialism’s Noisy Bodies”

Gabrielle Cornish (University of Miami)

Abstract: What exactly do monsters, teenage hooligans, and breakdancing have in common? As cultural restrictions in the Soviet Union began to relax during perestroika, musicians and artists began to test the limits of the human body by testing the boundary between living and dead. In this paper, I focus on three specific groups in the tight-knit Leningrad underground: the Necrorealists, an absurdist bunch of macabre performance artists led by Evgeny Yufit; the rock group Kino, led by frontman Viktor Tsoi; and Pop Mekhanika, an improvisatory orchestra led by composer and polymath Sergei Kuryokhin. By positioning the body—and, particularly, the youthful and often deformed body—in conflict with the normalcy of the state, these two groups performed their outsider status at the twilight of the Soviet Union. They embraced identifications of "monstrous" and "noisy" as ways of delineating themselves not only from official culture, but from Soviet—and, indeed, human—culture in general. By placing these two groups in their bio- and necropolitical contexts, I argue that their carnal, bodily, subhuman methods of performance became a way of asserting personal sovereignty within the existing power structures of late socialism. Through their absurdist art and music, these groups named the body as a site of many identities—normal, abnormal, human, nonhuman—and reclaimed it into their own sphere of personal control.