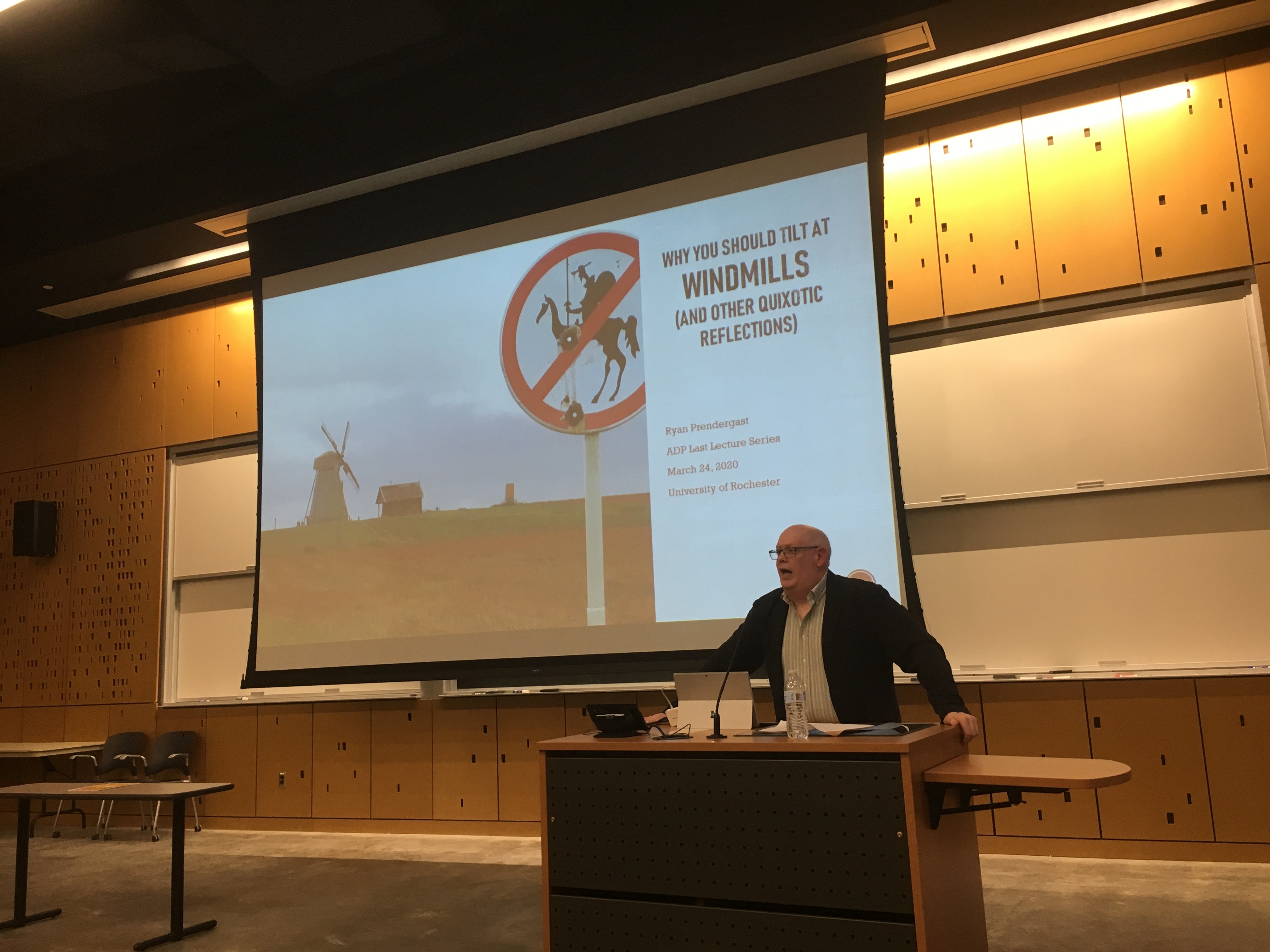

Why You Should Tilt at Windmills (and Other Quixotic Reflections) (excerpt)

Ryan Prendergast

Alpha Delta Phi Last Lecture Series

March 24, 2019

Let me start with a brief meditation on the phrase to “tilt at windmills” from my title. This idea, of course, is based on the famous episode where Don Quixote perceives the windmills in front of him to be giants and tilts at—or attacks them. As you might imagine, if you didn’t know already, he is not the victor in this battle. The text describes him as “broken and beaten” (I, 2). “Tilting at windmills” in contemporary parlance is typically understood as “attacking imaginary enemies or evils.” The expression and the iconic windmills are often seen in a variety of political cartoons and contexts.

While we are defining things, let me also take a moment to offer the definition of the key word from the parenthetical part of my title: quixotic. Merriam Webster defines the term as:

1: foolishly impractical especially in the pursuit of ideals especially : marked by rash lofty romantic ideas or extravagantly chivalrous action AND

2: capricious, unpredictable (m-w.com) It is a term that has been used since the early 18th century.

I want to tweak our understanding of the “tilting at windmills” expression, as well as the term quixotic for the sake of my lecture this afternoon— so it is more in line with the origin of both. That is to say for the term quixotic—we need to recall that is also means—or probably first or most precisely means, “of or related to Don Quixote.”---either the character or the novel.

I propose we take this different tack, since I view the pigeon-holing of Quixote as having addled brains as an oversimplification or even problematic misreading of this character. And if we allow ourselves to conceive of Quixote as both an inspirational and aspirational character, then maybe there are lessons to be learned from a 17th century book that has intrigued, challenged, and inspired authors and artists for centuries. For example Fyodor Dostoevsky stated: “A more profound and powerful work than this is not to be met with… [It is] the final and greatest utterance of the human mind.”

As for the idea of titling at windmills, I find it more suggestive to conceive of it as pursuing a goal when it does not seem easily attainable or when everyone around us questions our judgment. What follows are a number of points or tips that I suggest might help us live more quixotic lives—that is, more like the Don Quixote that I am presenting to you rather than the stereotypes you may have heard.

- Search for adventures—and for me this means going beyond something that is only undertaken for fun or for entertainment’s sake.

Don Quixote leaves his rather comfortable lifestyle as a country gentleman to pursue his goal of bringing back the lost practice of knight errantry. He risks life and limb, literally, because of his beliefs. While I am not encouraging you to risk your life, taking a risk, is something I do encourage. Consider leaving behind the familiar in pursuit of a goal or passion. Consider going against the recommendations of those we hold most dear or the prevailing beliefs of the time in the pursuit of justice. This may also include the need to ignore those naysayers who opine: “you will never be able to do X” or “you are not good enough to be successful at Y.” I’m sure you can call to mind myriad stories of past and present inventors, entrepreneurs, writers, or scientists who repeatedly were told that something was impossible or that they were destined to fail—and yet they persisted. They may have failed the first, second, or third or tenth time—yet they persisted and kept working hard. This in part, is what tilting at windmills or living quixotically means to me: pursuing your passions and persisting, even in the face of significant headwinds.

Here’s the catch. You could wind up molido (beat up or ground up) time and time again. But when we seek out adventures or challenges, we learn, we test our mettle. How do we ever know our limits if we never test them? Don Quixote’s adventures give him the smack down (literally) repeatedly—yet he ventures on—decidedly undeterred.

- Stand for something, perhaps, most importantly when people think you are ridiculous. Don Quixote’s desire to resuscitate knight-errantry is clearly an anachronic quest and one that leads him into a variety of clashes with people who try to fix or correct him. But what is so significant about the way he goes about his mission, is just how steadfast and unflinching he is. He has a code of conduct and he swears by it; he wants-among others things- to protect the defenseless and help uplift the downtrodden. He resists almost any temptation to diverge from these precepts and it helps him position himself in (and oftentimes against) the rest of the society. Quijote is quick to espouse his worldview to anyone who will listen. But what is key is that none of this is just rhetoric for him. He believes what he says, he has thought about the implications of his beliefs, and he can field questions eloquently when challenged (and when he doesn’t overreact and attack people with little or no warning—something I do not endorse, by the way).

Yes, being pigheaded or overzealous can be problematic---yet Don Quixote is not completely intransigent. For example, he and Sancho have a discussion about the difference between withdrawing (dignified/ a choice) and retreating (cowardly/incapable of standing up for oneself). This semantic back and forth leads to Don Quixote accept Sancho’s suggestion to hide out in the mountains to avoid punishment. DQ says: “…to keep you from saying I’m stubborn and never do as you advise me, this time I want to take your advice and withdraw myself from the violence you so much fear…” (Part 1, chapter 23)

This leads me to another essential aspect of living quixotically and number three on my list:

- Find your Sancho Panza. Who is Sancho Panza? No, he is not Pancho Villa, the general from the Mexican Revolution. He is Don Qujote’s neighbor turned squire turned friend and confidant. Am I saying everyone should have a squire? While that seems appealing, what I am suggesting is the need to have at least one person, an interlocutor, who will both support you and tell you when you’re being an idiot (even when—or especially when-- you don’t want to hear it, and even if you don’t listen all the time). As I have already mentioned, this person for Don Quixote is Sancho Panza. Their relationship is a complex and often challenging one, it has all the growing pains associated with the changing professional/interpersonal relationship they have. Moreover, it parallels a lot of the ups and downs of relationships that real people have, especially those who spend a lot of time together. Sancho does not always please Don Quijote with what he says and does, and Sancho blames Don Quixote for the physical and psychological injury they both experience. In fact, Don Quijote calls him an idiot and a fool on a variety of occasions. However, on others, he calls Sancho wise. Surprisingly, at one moment Sancho says that he thinks Don Quixote is the best person in the world. Sancho says: “he is not a bit tricky, he’s got a heart of gold—there’s nothing mean about him, he wants to be nice to everybody, he’s got no grudges at all…it’s because he is good-hearted that I love him with all my soul” (Part 2, chapter 13). What is even more telling about these comments by Sancho is that he makes them when Don Quixote is not within earshot and they are sandwiched between moments when Don Quixote has rebuked and insulted Sancho quite harshly.

Another example of the complex and amazing relationship these two characters have is seen in the second part of the novel. It characterizes the importance of having people around us who help us grow. Sancho says that Quijote’s words have been the manure that has fertilized the dry soil of his intellect: “ Some of your grace’s wisdom has got to rub off on me, for land that’s dry and unfruitful will give you good crops, if you put on enough manure, and weed it, and till it. I mean, your grace’s words have been like manure spread on the barren ground of my dry and uncultivated mind” (Part 2, Chapter 12). As you might imagine this is both a compliment and a dig. Sancho tells him he has benefitted immensely from his conversations and adventures with Don Quijote. As the same time, he is essentially telling Don Quixote that he is full of it (the it being manure). There are also multiple moments when Don Quixote adopts some of the rhetoric of Sancho as well. The mutual influence of Don Quixote and Sancho on one another has produced terms that some critics use to try to explain the evolution of these characters over the course of novel: they are the “quijotization” of Sancho and the “sanchification” of Don Quixote.

As you probably know already, and as you will continue to learn as you go through your life, true IRL friendships (vs. your social media “friends”/followers), family relationships, romantic relationships, and workplace interactions ebb and flow; some are lasting—others are situational. Not only that, it is rare to have people in your life with whom you can be completely honest when necessary and they can be honest with you. It is also rare to have someone you know well enough to be able to push their buttons or help them calm down. Do you have those people in your life whom you can both persuade or dissuade? With whom you can argue and then move on better for ? Who will tell you when you’re not thinking straight? If so, treasure them and cultivate those relationships. If you haven’t found this kind of person yet, do not despair. They are out there but building them and keeping them take work.

- Read and keep learning. Some critics characterize Don Quijote as a walking book, made up entirely of the chivalric tales that have determined who he is and how he is supposed to act. He appears to have memorized many of the details of these books that lined his library’s shelves. SO I would implore you to read---and think deeply about what you read. I encourage you to read for pleasure in addition to what you are assigned. It is essential to keep learning and reading, long after you complete your formal education.

Don Quijote appears to have a bottomless well from which to draw as he goes out in pursuit of his passion, his reason for being—his knightly adventures. He knows these texts like the back of his hand and can discuss them as an expert. There is no substitute for this kind of profound knowledge and there is, at least to my mind, no substitute for the exercise and habit of reading. AND REREADING. And what I mean by reading means going beyond scrolling through headlines, your twitter feed, etc. Read fiction and non-fiction that challenges you to stretch your brain (or perhaps makes you feel like your brain is melting). Commit to a habit of reading long-form journalism. I would also suggest you read from all points along the political/ideological spectrum as a way to find some kind of balance outside the echo chambers that cable news and social media feeds can create. Also realize that even when we read widely, there are still holes in our knowledge. For example, on Don Quixote’s first sally—before he has Sancho at his side, Don Quixote is informed that a knight must travel with several clean shirts and money (things that he never read in his books!)-àhence forth, he is better prepared. Even a so-called expert doesn’t know everything and has room to learn. He learns that there is a difference between theory and practice.

- Don’t take yourself too seriously. While Don Quijote is certainly very proud and does not like to be embarrassed (WHO DOES?) there is one section in the novel where he spends time deciding about which sort of madness he should adopt/imitate. Here he is choosing to act crazy. SLIDE MADNESS (This differs from the multiple times when people just laugh at him because of his beat up appearance and odd anachronistic rhetoric. )

What I mean to say here is that it is making a fool of oneself is not always a bad thing, even if it not on purpose. If I am to extrapolate this a bit, I am proposing that being able to laugh at oneself is an essential tool if we want to navigate the ups and downs that life has in store for each of us. This is especially true if we pursue adventures that put us in the position to put us in the position to be on a metaphorical tightrope or two.

- Write your story; recognize your worth!

Very early on in the novel, Don Quixote says the following to a neighbor: “I know who I am and I know that I not only can be those of whom I have spoken, but the twelve Peers of France and even the Nine Worthies, since all their heroic deeds put together or counted up each by each are surpassed by mine” (Part I, Ch. 5).

This declaration is thought provoking because he so often seems to be imitating models that have come from the books he has memorized and the plot lines he has absorbed. There is a certain kind of mold for a knight errant and this puts him on an established path. Yet, it becomes apparent rather quickly that this is not a path that he can easily travel. What Don Quixote recognizes is that he knows who he is in the present moment, but more importantly, that he suggests that is within his power to become someone or something else. He is able to imagine himself as a hero—as good as, nay even better than the models represented by his book. Inherent in this comment is the notion that he can shape or fashion himself. Some might say that that is another way to understand the term “quixotic.”

One of the first things that we read in the novel is the description of how Alonso Quijano, the middle-aged man who is part of the rural gentry, creates his new self, both through appearance and name—resulting in the creation of the persona DON QUIXOTE. He chooses to be reborn and to rethink the kind of person he will be going forward. This is not a simple process for him. His armor is old and rusty. The helmet is in disrepair and he does not have the skill to repair it completely. It takes a good amount of time for him to think of his new name and a name for his horse. As time passes, Sancho gives him his first epithet, imposing on Don Quijote the moniker: THE KNIGHT OF THE SAD FACE. It is not until many adventures later that Don Quixote takes the reigns of his identity back entirely and renames himself THE KNIGHT OF THE LIONS.

The takeaways that I see here are:

1) it never too late to try to change who you are and

2) while at times the world attempts to label us or limit us, we must always strive to reclaim who we are. Resist being defined by others, and fight to create a life that is uniquely ours.