Alumni Profiles

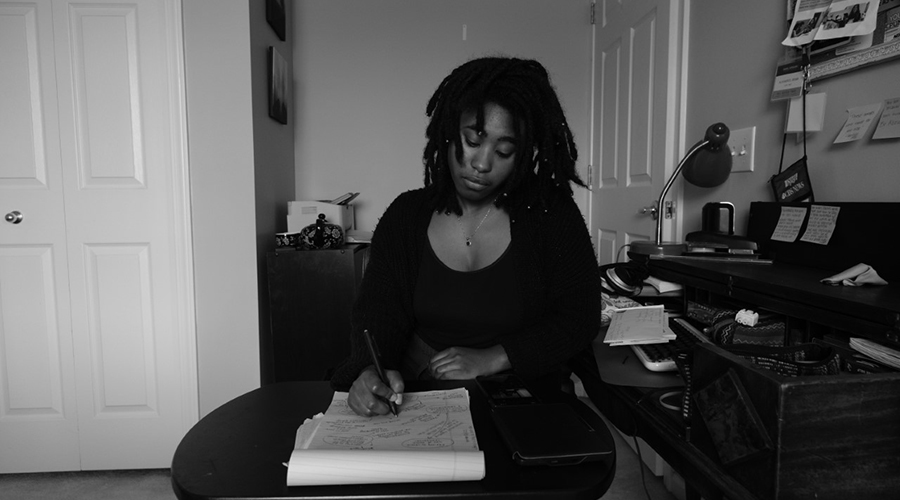

Alexandria Brown

Class of 2018

Alexandria currently works as Digital Associate with the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition where she engages voter turnout in communities across Michigan. Previously, she was the Managing Editor of Flintside from December 2019 until June 2020. She still contributes as a freelance, multimedia reporter with the publication and recently began building her photography business, Xandr B. Photography LLC. She sees a long-term future working within media and hopes to move abroad in the future. Some of Alexandria’s recent publications are listed at the end of this profile.

Living in Rochester, I never really felt like I left home. The demographic makeup was similar to where I was raised, in Flint, Michigan, and the issues of low-funded public schools and other infrastructure still vignetted the campus. My grandparents raised me in a suburb south of the city but a majority of my time and early memories came from the industrial dustbowl called Flint. I was born there. I went to a privatized school there. I went to my great aunt’s Cherry Street holiday dinners there and it always sort of felt like I was being protected from something. Looking back, I know it was the sights of poverty, violence, and scarcity. Conversations about the city were always full of the lament of how it had been hollowed out and folks just couldn’t keep it together—their rusted homes, their dandelion-riddled lawns, their schools, their city. It wasn’t like it used to be. That was the echo chamber. This, in combination with personal issues I had yet to process, made me grateful for the 346 miles of distance the University of Rochester gave me. So when the Flint Water Crisis bubbled out in 2014, the news didn’t hit me as hard as it did some of my friends who asked me about it. “Hey, aren’t you from around there? Did you know this was happening?”

By this point, I had only taken my first environmental humanities course and I struggled to feel any of the horror response the injustice warranted. Besides, I live in the suburbs, I thought, it's not fair for me to speak. Taking environmental justice courses changed that way of thinking for me.

Before coming to college, I had never given much thought to the environment. Such conversations signaled for me, with my relatively religious and conservative background, imagery of “tree huggers,” hippies, and at worst tree-hugging hippies. It was my understanding back then that this planet was for the use and benefit of mankind, not the other way around. I never considered environmental issues as an analysis of our relationship to what’s around us and of ideas in our minds that create justifications for exploiting that relationship.

Environmental issues seemed even more out of touch for me as a Black person. Nature was wilderness. A location of sharecropping labor, King Cotton, and strange fruit. It was a landscape of struggle.

Though this is true in some ways, it also informed the subtle ways in which I and my family practiced sustainability, such as the boxes filled with grocery bags for reuse, rewashing take-home containers for food storage, or going to second-hand stores for our clothes. I listened to my grandma tell me stories about the garden her mother grew and how berries could be freshly picked off the bush—how she helped her mother can the fruits throughout the year, especially in anticipation of not being able to buy their own food.

I saw parts of myself in the journalistic and fictive literature we read. The written reflections we produced from the classes forced me to look closely at my ideologies, my practices, my history, my biases, and my environmental blindspots to see how narratives of capitalism, productivity, isolation, violence, and entitlement served the greater purpose of separating me from my perception of nature. Through journalism and history, I could make the connection of exploitation of the environment to the historical extraction of labor from Black Americans and other minorities in this country. I read about the strategic neglect and poisoning of those populations with little consequence—like the environmental injustice done to Flint—and how through environmental justice movements they made their voices heard.

As news continued to document the poisoning of Flint, it was those sorts of voices that I heard ringing out beyond the door of memory I had been reluctant to open.

As news continued to document the poisoning of Flint, it was those sorts of voices that I heard ringing out beyond the door of memory I had been reluctant to open.

I had to remember the gated schools I attended where I was passively guided to never look too closely outside at what laid beyond. I reflected on the tuition paywall that mentally seperated me to make me think I was systematically immune to my Black body. And I pondered on the sobering realization that my great aunt on Cherry Street was living bottle to bottle. How many of us were?

I had earned enough privilege through my education to get away, but there were swaths of people, people who were victims of their circumstances, who could not. While they went through a terrifying historical disappointment, those like me watched from the outside. Flint sat on the broken seam of the American Dream and little did I know that I had taken a thread with me that would bring me back, and that was journalism.

I returned back to the Flint area to document a city largely characterized by its will to survive. I found and wanted to platform humanity there instead. From what I’ve learned, acts of environmental injustice comes easy when those who have the injustice inflicted on them aren’t seen as human beings, but instead a consequence—a reminder of what can happen to you if you walk a certain road, if you don’t work hard enough, or if you don’t exploit in the way society prioritizes.

Ever since I’ve been back, I’ve written for two independent local publications, Flintside and Flintbeat. I wrote about and photographed Flint food deserts. I covered water filtering technologies. I covered neighborhood efforts of people determined to make the city home for their children and grandchildren through pocket parks, placemaking, and beautification efforts.

I thought that in order to be an (environmental) journalist, I should be covering floods, hurricanes, or tornado destruction. Although that coverage is important, it’s more challenging and long-lasting to cover the rust and the dandelions. Rust is all those left behind after a great metal machine uproots itself and the economy out of their city. There are folks left behind still fighting, defining, and redefining that space. They tend to be dandelions, historically defined as weeds and characterized as an aesthetic eyesore despite their inherent value, and face poisonous concoctions to oust them from their landscape. These things can happen in places with lots of pastures and places filled with cement because the pollution doesn’t always reflect immediately in the dirty water, the broken levees, or the chemical plant in a backyard, it starts in people’s minds and what they are willing to perpetuate.

Without taking environmental humanities courses, I wouldn’t be as sensitive and awakened to where I came from. I wouldn’t have had the tools to etch out those stories. I wouldn’t have ever thought to look and become acquainted with the rust and the dandelions.

Some links to Alexandria’s journalism work

Flint water crisis persists, still no grocery store for city’s north side

How the Water Box is fostering community trust across Flint

Actor Hill Harper joins activists to equip Flint's Haskell Community Center with new water filter

The ruralization of Flint's Civic Park neighborhood

One woman's fight to save Flint's hidden park

'This is home': Why these longtime residents stayed in North Flint