Sonata in the Flower City: Rochester’s Place in the Life of Paderewski

Celebrating the 150th Anniversary of a Great Musician’s Birth

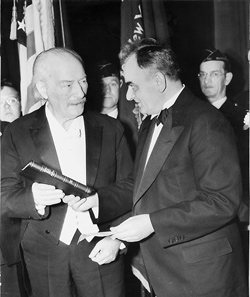

Paderewski and Felerski

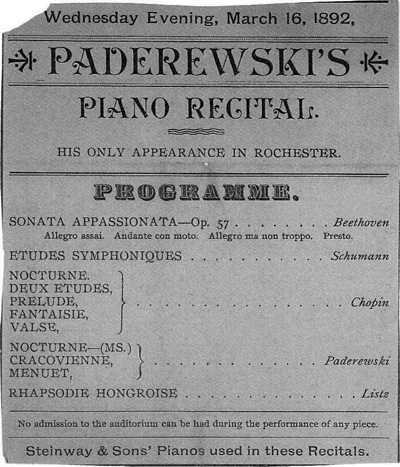

Paderewski first performed in Rochester in 1892, presenting original works as well as selections from Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin, and Liszt on his second US tour. He returned to Rochester several times during his career, earning both critical acclaim and popular affection. In 1916, a reviewer for the Post Express applauded the “fine intelligence,” “wonderful minuteness of effect,” and “high plane of emotional power” evident in his playing. In 1928, a Democrat and Chronicle reviewer marveled at the poetic effect of Paderewski’s all-Chopin program, noting that “Paderewski’s plummet of interpretation of Chopin goes deeper and finds certain beautiful musical detail, sounds the full spirit of the music more completely than other interpretations do.” Rochester concert halls were always filled to capacity for his performances, with chairs often set up on stage to accommodate an overflow crowd.

Among Rochester’s citizens of Polish descent, Paderewski’s appearances generated great excitement and immense pride. For them, he embodied the spirit and culture of their homeland, particularly and poignantly during the period before the First World War when Poland was under foreign rule. Whenever Paderewski visited, Rochester’s Polish community organized a special welcome and often presented him with a gift conveying their regard, such as a pair of binoculars made by Bausch & Lomb, inscribed “From the Poles of Rochester to the Master of the Piano,” in 1932. Leading members of the Polish community invited him to take tea with them and the “modern immortal” graciously obliged, enjoying refreshments at modest homes in Polish Town.

Paderewski's program, 1892

Most dramatically, Paderewski brought the city’s attention to Poland’s cause in June 1918 when the local Polish Citizens Committee arranged for him to address the Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber was “stormed,” the press reported, by “persons not only from this city but from many surrounding towns who filled the main floor and the balcony of the hall to overflowing.” Police officers monitored the crowd pushing into the foyer and, despite an effort to fit additional guests in the galleries, hundreds who waited in hope of being seated had to be turned away. Paderewski’s speech was riveting and effective, leading the War Chest to allocate $100,000 for Polish relief on behalf of the people of Rochester. Supplementing this generous donation was an additional $14,000 raised by the city’s citizens of Polish descent.

After the war, Paderewski served as Poland’s Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and represented his homeland at the League of Nations. His career in politics was brief, however, and the master of the piano returned to music in 1922. His concert tours brought him again to Rochester where he was hailed as “one of the few picturesque figures left to us in these matter-of-fact days.” In 1923, he literally inscribed his name on local history when he became the first visitor to sign the guest book at the Eastman School of Music, offering his compliments to the school and to its “noble and generous founder.”

Paderewski continued to draw standing-room-only crowds through the 1930s. When he appeared here in May 1939, he was nearly 80 years old and it was clear there would not be many more performances. “Time and worldly sorrows have taken their toll of the man,” wrote one music critic, but he “still is able by his supreme musicianship to go through with an exacting program and to rouse his audience by the inspiration of his playing…. Last night’s experience is one that will never be forgotten by those present. There never will be another Paderewski.”

After the concert, which drew two encores, members of the local Polish community met Paderewski backstage “in a brief ceremony so touching that tears came to the eyes of several onlookers.” A delegation from the Polonia Civic Centre greeted him and presented him with a copy of the History of the Polish People in Rochester. Paderewski acknowledged the heartfelt gift and thanked the group in Polish, then departed for the New York Central Railroad yard where a train was waiting to take him to his next performance at Madison Square Garden.

That performance never took place, and Rochester “won a sad and significant” distinction as the last city in which Paderewski played publicly. The pianist collapsed minutes before his New York City concert and departed, ailing, for his home in Switzerland as the remaining dates on the tour were cancelled. Many in Rochester would long remember his final appearance here, including workers at the New York Central yard who heard him practicing on the piano in his private car. “The melody he sent forth from the car gave yard hands many moments of pleasure,” the Times Union noted, “moments for which many music lovers would have sacrificed much.”

In tribute from a city that had longstanding affection for him, Rochesterians organized a Paderewski Testimonial Fund shortly after his death in 1941. The committee, headed by Dr. Howard Hanson of the Eastman School of Music and including representatives of Rochester’s Polish community, designated the money raised for the Paderewski Polish Hospital in Edinburgh, which served Polish refugees in Britain during World War II. Surely, the master of the piano and Polish patriot would have been moved by this expression of deep regard from his friends in the Flower City.

Kathleen Urbanic is archivist and historian for Rochester Polonia