Fake News Susceptibility – Who Spreads Disinformation and Who Can Fall Into It?

By Malwina Popiołek

Misleading or false information has been present in the mass media since its beginning and has been an effective tool of achieving specific goals, not only in political communication, but also in advertising. In recent years, however, we have been talking about misinformation more and more, and this may be due to a change in our communication habits. It is the widespread use of social media that has caused an increase in interest in the issue of fake news, because today it is much easier to create and spread it than it was a few decades ago.

In 2016, it was reported in the media that during the U.S. presidential election, fake election stories likely generated more engagement (i.e., shares, reactions and comments) on Facebook than the top 20 stories from major news outlets such as the New York Times, Washington Post and NBC News (Hughes & Waismel-Manor, 2021). Although researchers were divided about how much the fake news generated at the time influenced the final outcome of the election, the very fact of an organized covert attempt to manipulate public opinion generated strong emotions and heated discussions, not only in the United States.

In 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, disinformation processes became particularly apparent, and the issue of fake news attracted the attention not only of researchers or observers of social life, but also of governments and public institutions. It has begun to be recognized that fake news has demonstrable social effects and can not only influence our views and decisions, but significantly impede many important public tasks, such as public health management.

Interest in this topic is not diminishing, especially since disinformation has become a tool of hybrid warfare. Given the current political situation in the world, especially after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the topic of fake news is increasingly important, and knowledge of it seems essential for a proper understanding of information processes in the modern world.

What is Fake News

Focusing on the concept of fake news, it would be appropriate to refer to its contemporary definitions. The literature distinguishes two main approaches to fake news (Zhou & Zafarani, 2018):

- broad definitions of the issue - in this view, any media content that is reported as fact, but is not based on fact, or contains false elements, can be considered fake news.

- narrow definitions of the issue - in this case, the focus shifts to the intention of the sender. If it is false by intention, we say that we are dealing with fake news.

In addition to the distinction between false and fabricated news, the “newsiness” of the news is also an important definitional issue. This is because not every piece of information can be considered news at all. Newsiness is important especially from the perspective of traditional news media. Thus, in the definitional context, it is worth remembering that not all false media content is also news.

Considering the communication effect, we mostly talk about fake news in the context of misleading the recipient. However, as already mentioned, this effect can also be achieved by using truthful news. Accordingly, researchers of the issue distinguish various categories referring precisely to the process of communication, rather than to individual news items.

This, moreover, has been noted and described by Claire Wardle. According to her, when we talk about fake news, we mean more than the news itself, we mean the entire information ecosystem. The whole spectrum of different types of irregularities or distortions in the process of mass communication, including both intentional and unintentional introduction of false, or true but misleading information into circulation (Wardle, 2017). In doing so, the author points out that in order to understand this complexity, it is necessary to distinguish three elements:

- the different types of content that are created and shared;

- the motivations of the entities that create this content;

- the ways in which this content is disseminated.

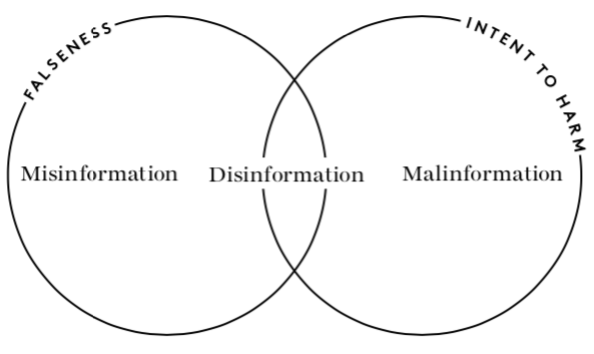

Often we use the term “fake news” to describe content that is not false at all, but merely set in a context that gives us misleading associations. News, therefore, does not have to be fabricated to mislead us (Wardle, 2020). The author therefore distinguished three categories of communication processes involved in communicating untruths: disinformation, misinformation and malinformation. Below is a figure that represents these three categories:

Source: Wardle, 2020 [Retrieved from: https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/understanding-information-disorder/].

As can be seen here, when considering the differences two things are important: the consistency of the content with the facts and the intention of the sender. Intended to cause harm, the information does not have to be untrue, and also, the motivating factor for the sender to publish untruths is not necessarily the intention to cause harm. Sometimes it is, for example, the result of insufficiently good journalistic research. To organize the argument, it is worth defining the various processes in more detail (Wardle, 2020):

- Disinformation is a process in which false content is designed, shared and disseminated intentionally, often with the goal of causing harm. Disinformation can also be motivated by other reasons, such as a desire to make money, a desire to gain political influence, or a desire to create confusion or information chaos;

- Misinformation occurs when there is no clear intention to mislead. For example, when the person spreading false content does not realize that the message is false or misleading. Misinformation is often the result of socio-psychological factors, e.g., fear of exclusion;

- Malinformation refers to the process by which true information is made available with the intent to cause harm. An example of this is when agents of foreign intelligence agencies hack into the private email accounts of public figures and disseminate the information thus obtained, with the goal of causing harm.

Who creates and spreads fake news

The sources of false information are diverse. The first source is deliberate action, often by state actors as a tool of a hybrid warfare, when false information is created through so-called “troll farms,” which are paid agencies that specialize in creating this type of content. Another source is actors and entities earning clicks who spread false, sensational news for profit. It also happens that untrue content comes from ideologically committed groups or organizations that, through exaggerated or completely untrue news, want to gain new supporters or make a name for themselves in the public space (e.g., anti-vaccine movements). It happens that various satirical sources are taken too seriously and the fabricated humorous materials created by them, are made available online as the truth. Potentially, fake news can also be deliberately introduced into the information space by researchers to study the processes involved in its dissemination. Finally, as access to the Internet is becoming more widespread, and it is relatively easy to create and disseminate content, it is sometimes the case that fake news is the result of mentally disturbed individuals who may have a distorted perception of reality.

Sometimes it happens that false information is published in professional news media. In 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic in a research team at the Institute of Culture at the Jagiellonian University, we conducted a study to see how often false information about the coronavirus appeared in the mainstream media. It turned out that of the 101 fake news stories then circulating in the Polish Internet space between January and September 2020, as many as 25 also appeared in the news media. This accounted for nearly 25% of all identified fake news at the time. The vast majority of these were the result of misinformation (Popiołek et al., 2021).

While the original sources of fake news may be such as those mentioned above, it is not always easy to determine the original sender of the fake content. Recent studies further suggest that organic traffic, rather than bots, dominates the spread of disinformation. Fake news is spread by personal profiles, as seen, for example, especially during elections. However, bots, are prominent in this regard in the early stages of virus spread and attack influential users. Some users act as “super spreaders,” initiating large cascades of diffusion, while others have little influence. Individuals retweeting fake news often form tightly knit groups, helping messages spread through their networks (Dourado, 2023).

Who believes in fake news

Once it is known who creates and spreads fake news, the question becomes, who believes it and why? Any of us could fall victim to disinformation. However, are there systematic psychological or demographic characteristics that predispose one to be more susceptible to disinformation? The answer to this question is not simple, for a number of reasons.

First, this type of correlation is very difficult to study so as to provide clear answers. Media sources of information, are not always the only determinants of our decisions. Second, it is very difficult to precisely measure the cognitive process itself that occurs under the influence of consuming fake news.

As the research shows (Beauvais, 2022), susceptibility to fake news is related to the ecosystem of the contemporary media and social network sites, including, for example, the rapid spread of fake content, unfiltered information on platforms, and the fact that audiences share such content organically, so that we often receive it from people that we trust. Cognitive factors commonly known in psychology, such as confirmation bias, political views, previous exposure to a given piece of information and intuitive thinking, also play an important role. A low level of education and scientific knowledge may also predispose one to greater susceptibility to fake content. Psychological factors include attraction to news, strong emotional arousal and the emotionally charged content of fake news.

We know that the human brain works in such a way that we have cognitive biases. As a result, it is also known that political bias can lead us to more readily accept content, including news stories, that are in line with our political beliefs. This is an effect that has been observed among media audiences for a long time. Our judgment can be distorted when we don't readily accede to content and news that doesn't conform to our beliefs, ignore them, and anchor ourselves to content that suits us better. Contemporary research on fake news on the Internet confirms these theories, but also develops and complements them.

Emotions seem to play a key role here, as many studies show that strong emotional arousal and reliance on emotions instead of reason increase susceptibility to fake news. These factors combine with information bubbles and pressure from interest groups to reinforce the acceptance of fake news (Bryanov & Vziatysheva, 2021; Martel et al., 2020; Pennycook & Rand, 2021). False content is often designed precisely to trigger emotions. It is best to practice restraint, not to share this content with others, not to duplicate it, and not to react to it.

Conclusion

Although it is difficult to find a universal method of shielding oneself from fake news, it can be said that having knowledge about disinformation undoubtedly helps us to understand that we are exposed to it every day—especially when we rely primarily on internet sources for information. Research shows that debunking alone is not fully effective in combating disinformation; education—learning to recognize disinformation and practicing critical media consumption—appears to offer better protection against its harmful effects.

Without an understanding of cognitive processes and without media literacy, we can easily fall into the disinformation trap. Moreover, it seems essential that we actively desire the truth and expect it in public discourse—from the media, from politicians, and from public institutions. Social acceptance of falsehood, a lack of reaction, or, granting legitimacy and support to those who spread untruths can undermine the functioning and foundations of a democratic system.

Sources

Beauvais, C. (2022). Fake news: Why do we believe it? Joint Bone Spine, 89(4), 105371.

Bryanov, K., & Vziatysheva, V. (2021). Determinants of individuals’ belief in fake news: A scoping review determinants of belief in fake news. PLoS One, 16(6), e0253717.

Dourado, T. (2023). Who posts fake news? Authentic and inauthentic spreaders of fabricated news on Facebook and Twitter. Journalism Practice, 17(10), 2103–2122.

Hughes, H. C., & Waismel-Manor, I. (2021). The Macedonian Fake News Industry and the 2016 US Election. PS: Political Science & Politics, 54(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000992

Martel, C., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Reliance on emotion promotes belief in fake news. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 5, 1–20.

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402.

Popiołek, M., Hapek, M., & Barańska, M. (2021). Infodemia–an analysis of fake news in Polish news portals and traditional media during the coronavirus pandemic. Communication & Society, 34(4), 81–98.

Wardle, C. (2017). Fake News. It’s Complicated. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews.com/fake-news-complicated/

Zhou, X., & Zafarani, R. (2018). A Survey of Fake News: Fundamental Theories, Detection Methods, and Opportunities. https://doi.org/10.1145/3395046

Dr. Malwina Popiołek, Associate Professor, Department of Management and Social Communication, Institute of Culture, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, was Skalny Visiting Professor in Fall 2024 and taught International Relations 243W, „Media and Social Media in Poland and America.”