Inside an Authoritarian State

By Guzel Garifullina

When talking about authoritarian regimes, we often focus on such elements of political life as elections, propaganda, or repression. These are all fascinating topics, but we also know that these do not describe the bulk of the interactions between the citizens of these countries and the state. An ordinary citizen under any regime builds a lot of their attitudes toward the political order based on daily experiences at the local level and in a bureaucrat's office. Such experiences often form long-term grievances or loyalties that shape the society and can spark or stifle significant changes, create space for reform or undermine regime legitimacy.

This motivates my interest in subnational politics and bureaucratic politics in autocracies. How do authoritarian institutions at the subnational level affect citizens' desire to pursue a political career? How does politics seep into the street-level bureaucracy? What are the incentives that an authoritarian bureaucracy creates for regular bureaucrats? These are some of the research questions I have addressed in my work. I focus on Russia, which provides an ample opportunity to explore cross-regional variation in the practices of the state actors due to the country's size and heterogeneity.

To answer these questions, I combine various methods and data sources. Some of my recent work uses the survey of street-level bureaucrats in Russia1 to explore the incentives and practices driving bureaucrats' behavior. For example, we know that informal practices play a major role in Russian politics. Social ties within the elite have been shown to determine major political appointments. Examples include four governors appointed in 2019 who used to work in Putin's personal security and several sons of powerful officials heading state corporations. What does that mean for the lower level of governance? From research, we know that bureaucracy based on merit has a variety of positive outcomes – including minimizing corruption and increasing government efficiency – that would help the state maintain its public support and are therefore in the interests of the regime. I argue that the informal nature of politics will seep into the bureaucratic apparatus, and we will see merit being less important than personal connections even for medium-level promotions at the regional and municipal levels. That matters because promotion based on personal connections will keep away high-quality and reform-oriented civil servants and demotivate bureaucrats who can't see a possibility of growth despite their efforts.

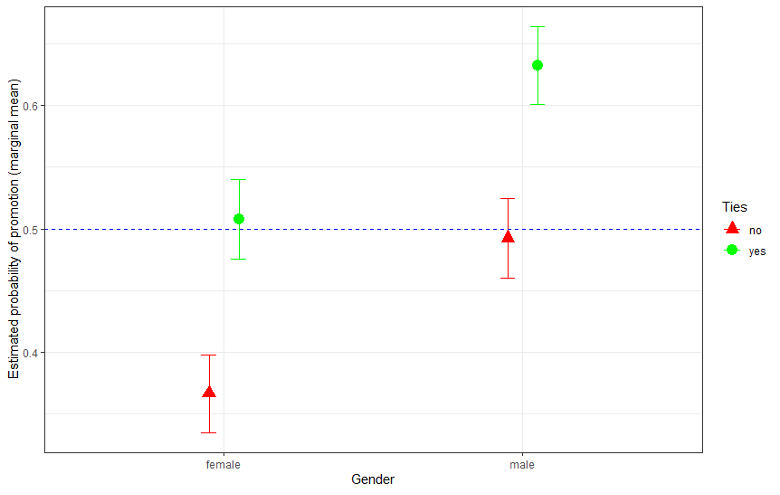

In the survey, I ask the bureaucrats themselves about the promotions system – and I use a method specifically designed to elicit truthful responses to sensitive questions. The respondents compare two hypothetical candidates for promotion, each described by a set of attributes, and indicate which one is more likely to be advanced – based on their own experiences and observations about the system they work in. Using the results, I can estimate how important each attribute is for promotion, on average. The results are very clear: personal connections to the future supervisor are among the most important factors predicting promotion. Having such ties increases the probability of being promoted by almost 15 percentage points. While education and experience matter, they are not enough on their own. I also uncover some patterns that are particularly troubling once we put them against the composition of the Russian civil service. An overwhelming majority of the regional and municipal bureaucrats and 86% of our sample are women. Yet these same respondents admit that being a woman is a great disadvantage for promotion. The illustration here (Graph 1) clearly shows both the importance of personal connections for promotion – and how even playing by the rules of the game and developing such ties is not enough for a woman to close the gender gap. A woman with personal connections is significantly more likely to get promoted than a woman without them – but is indistinguishable from a man without such ties, and way behind a man with personal connections.

Note: Marginal mean of 0.5 indicates that a candidate with such characteristic is as likely to be selected as if the choice were made randomly (no clear preference)

The period I spent in Rochester as a Skalny Center Postdoctoral Fellow provided me with ample opportunities to advance my research and explore new topics. Besides working on my papers, I presented my ongoing research at conferences and, in cooperation with several colleagues, organized a two-day workshop dedicated to Eurasian political economy at the Midwest Political Science Association conference. I had time to design another survey of civil servants in Russia, to reproduce the results we received from one Russian region in an equally detailed study in another region. Furthermore, I had an opportunity to teach two undergraduate classes – Russian Politics in the fall and Comparative Subnational Politics in the spring. I found the second course particularly rewarding as I haven't seen such an undergraduate course taught anywhere else, and developed it to share my passion for local politics in diverse political environments with the students. The course focused on non-Western countries by design, as they are less likely to be covered in other discussions of federalism or decentralization the students may be exposed to. An essential element of this course was the breaking up of the written assignment into regular submissions, in which the students followed their chosen country as we progressed through the topics and independently developed their own expertise, culminating in a final research paper. I enjoyed the discussions we had in class and the way they connected to the students' interests and coursework on the topics of poverty and development, among other things. We discussed how citizens experience politics locally, how institutions and elites can affect these experiences, and how local politics can shape a country's development – be it economic development or political transformations.

Russia's political future is increasingly uncertain, and most observers agree that there are major changes ahead as the regime's highly personalized nature makes it vulnerable in the long run. Overcoming the dominance of informal institutions would be one of the primary goals for successful and sustainable political and governance reforms – which makes the research on the practices of governance in Russia so exciting.

Footnotes

Guzel Garifullina is the Skalny post-doctoral fellow for the 2021-2022 academic year.