Polish political memes as an example of uncreative writing

by Piotr Marecki

The biologist Richard Dawkins proposed the term “meme” in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, in which he used the theory of evolution as an analogy for cultural change. In his understanding, memes were “small cultural units of transmission, analogous to genes, that spread from person to person by copying or imitation” (Shifman 2016: 9). The units he had in mind were musical themes, trends, catchphrases, or abstract concepts, such as the idea of God. Limor Shifman notes in his book, Memes in Digital Culture, that the term had already been used by the Austrian sociologist Ewald Heing, so it appears that the term itself is a meme, although Dawkins was not conscious that it had been used before. In current usage, the term refers to pictures with captions that spread on the internet, which have become an international phenomenon that crosses linguistic barriers. Memes are defined by replication, change, spreading, remaking and remixing. Memes compete for attention, and depending on their cultural milieu, some memes reproduce themselves, while others disappear. Memes depend on context, so there are no universal memes that are understandable to everyone.

Memes are just funny pictures with funny captions, but this digital genre has a big influence on the social sphere. I treat memes as an example of a local digital culture, a kind of digital genre, difficult to translate into other cultural contexts. As an example of the prominence of memes, one of the biggest Polish political parties, .Nowoczesna (.Modern), revealed that it spends more of its funds on memes than on PR. Memes have become a popular journalistic genre (often superseding the traditional journalistic genres) and a tool for original expression. The term “memiarz” (memer,) applied to the craft of making memes, has already found its way into the Polish language. There are lots of other interesting phenomena from the Polish memosphere, but here I will describe some memes on political subjects.

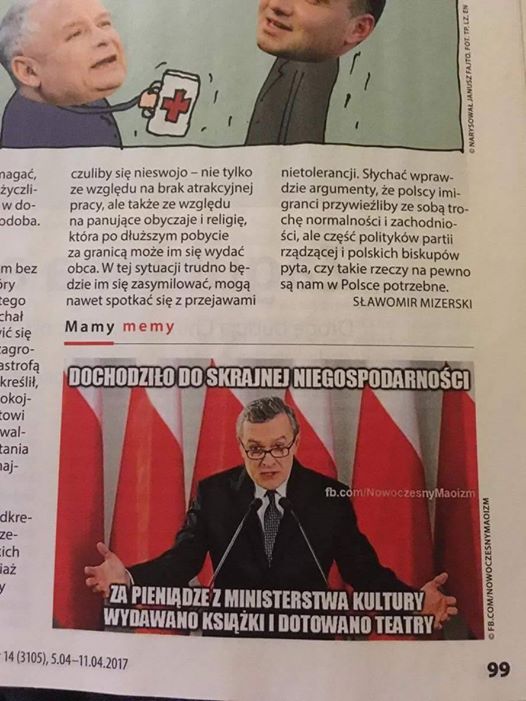

Memes replacing journalism. The “Mamy memy” (lit. “We’ve got memes”) section in the popular Polish magazine “Polityka.” Pictured is the Minister of Culture in the Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) administration, speaking about the previous government: “The scale of mismanagement was enormous. The Ministry of Culture’s funds were spent on publishing books and subsidizing theaters.”

Memes are a digital genre because they spread through viral transmission. It is through the digital media that memes are being replicated and remade, often instantly. Another feature of the memes is their uncreativity. Memes are an example of a radically constrained form. A memer has at his or her disposal an image, usually one, sometimes a collage, on which he or she can superimpose a small amount of text. Usually neither the image nor the text is the memer’s individual input. An author of a meme usually bases it on images stolen from the internet, often stock pictures that can be bought for various purposes, or journalistic photography. The text published by a memer is also rooted and recognizable in a given community. Therefore, memes, like many digital genres, are examples of so-called “uncreative writing,” as described by Kenneth Goldsmith in his 2011 book with that title.

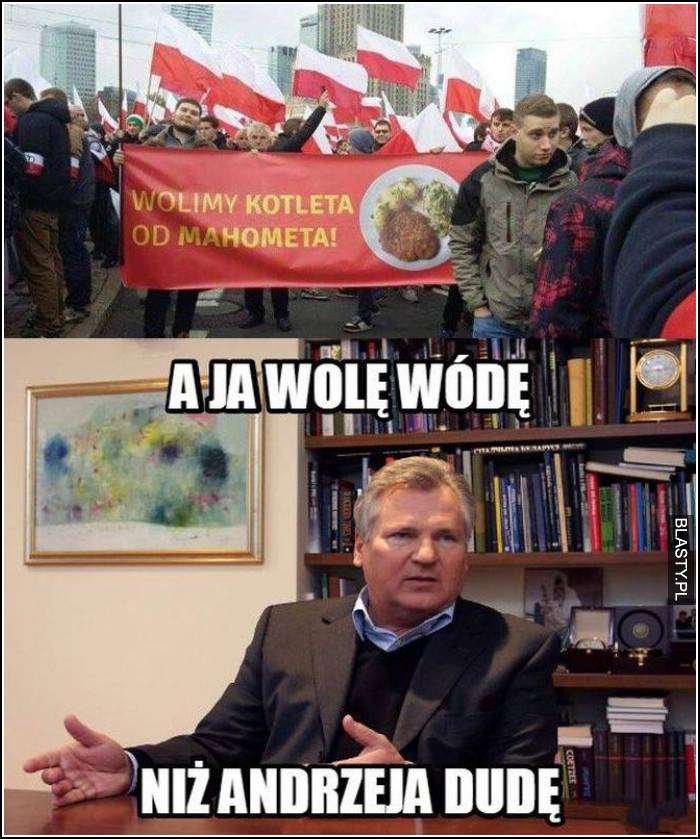

Although there are some examples of international memes, most memes make use of images and texts that are local and recognizable within a given community. As an example, in Poland, after the March of Independence organized in 2015, a very popular phrase was, “Wolimy kotleta od Mahometa” (lit. “We prefer a cutlet to Muhammed.”) This was an example of the xenophobic tendencies in Polish society that, among other things, led to the victory of the far-right Law and Justice Party. The images circulating in the media were those of “the real Poles,” carrying a banner with the image of the aforementioned famous Polish dish, accompanied of course by boiled potatoes and cooked cabbage, and surrounded by white-and-red flags. In a smaller font was written, “Traditional Polish family dinner, on Sunday after church.” While journalists and the media were captivated by this phrase, the response of the memers, who remade the motto in many different ways, appeared almost instantly. The most famous example is, “A ja wolę wódę niż Andrzeja Dudę” (lit. “But I prefer vodka to Andrzej Duda,”) illustrated by a picture of Aleksander Kwaśniewski, the former president of Poland, who was known for his drinking, and referring to Andrzej Duda, the current Law and Justice president. Outside of this context the caption on the meme is simply incomprehensible.

The popularity of memes is visible in the numbers, especially when compared to the traditional press. For example, the most popular Polish meme page on Facebook, Demotywatory (Demotivators) has 1,897,103 likes; Kwejk (website similar to 9gag.com) has 1,775,694 likes, and Sok z buraka (lit. The Beetroot Juice) has 558,507 likes; while among the newspapers considered the most influential, Gazeta Wyborcza has 480,134 likes; Rzeczpospolita has 93,959 likes; the weekly Polityka has 259,099 likes; and the most important rightist weekly magazine, Wpolityce, has 85,720 likes. The popularity of memes is therefore several times larger than the impact of the most influential media outlets. In addition, memes are passed on through the internet to further recipients, giving them much broader exposure.

The most popular memes from pages like Demotywatory or Kwejk are not challenging, and can readily be understood by any viewer who understands the Polish context.

An example of the meme from the Demotywatory website; Lech Walesa claims that “Trump is copying me,” and the hog responds by laughing.

An example of the meme from Sok z Buraka fanpage. President Duda says “If the bill isn’t prepared properly, of course I will veto it!” Jarosław Kaczyński laughs [it is widely understood that the President would sign anything that the leader of the Law and Justice wants him to.]

The second category consists of memes that are a little more sophisticated. Often created by artists and journalists, they are of better quality and require some decoding skill. While not for everyone, they are still very popular. Fanpages like Piękni chłopcy prawicy (lit. Pretty rightist boys) or Nowoczesny maoizm (Modern Maoism) have 35,734 and 52,202 likes, respectively, and have built their popularity on the genre of political satire. The memes they share exploit well-known public figures, their flaws and personal appearances, in the manner of sketch-comedy shows or satirical texts. For example, the phrase “piąteczek” (diminutive form of “piątek” - “Friday”), which stands for the end of the workweek, has become associated with the famous drinker, President Kwaśniewski, to the degree that it has become a tradition to share a meme of Kwasniewski and a virtual drink before leaving work on Friday afternoon.

“Will I forever remain a Friday meme?”

Ryszard Petru, the leader of the .Modern party, has become the opposite of Kwasniewski, as an example of neoliberal faith in hard work. Following the rise in .Modern’s popularity, one of the most popular Polish meme pages, Hipsterski maoizm (Hipster Maoism) changed its name to Nowoczesny maoizm (Modern Maoism) to lampoon the party’s name. One of its popular memes, for example, was an image of Petru standing next to Leszek Balcerowicz, the former Minister of Finance in the early 1990s who became an icon of Polish neoliberal reforms, encouraging hard work. The meme is frequently shared on Monday mornings, at the beginning of the work week. The caption of one such meme was, “Kto rano wstaje, temu niewidzialna ręka daje” (“The invisible hand [of the market] helps the early riser”), which was a twist on the popular Polish phrase, “God helps the early riser.” The implication is that God, who is, after all, important in a Catholic country, has been replaced by the free market.

Memes ridicule every political orientation. Donald Tusk, the former Prime Minister, the leader of the Civic Platform Party and the President of the European Union, cultivates an image as “an average Pole,” who does his own shopping and drives his own car (which is not common for the leaders of other parties.) This kind of PR, like pictures showing him eating a cheap hot dog at a gas station, is a subject of ridicule for the memers. Modern Maoism refers to a common problem faced by Poles who come back to Poland after working for a living abroad, and are not able to find employment. The caption says: “When you come back from abroad, but you can’t find a job.”

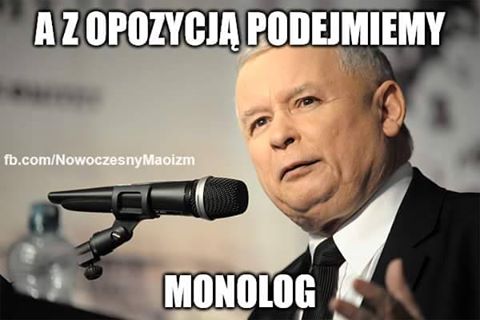

In a similar way, memes are far from creating a friendly image for Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the far-right Law and Justice Party. He is known for his inability to make agreements with the opposition, and he is often depicted with a sour face, appearing implacable and disconnected from reality. The example below bears the caption, “We are willing to start a monologue with the opposition.”

Memes also describe politicians’ relationships with each other. For example, the meme below contains in the top frame the famous “papal” photo of Donald Tusk (Tusk, like the Pope John Paul II, appeared in a window to greet his fellow countrymen gathered outside), and juxtaposes it with a photo of Kaczynski, who is known for his vindictiveness, with a rifle. It needs no caption, and it communicates a lot about the personalities, relationship and aspirations of the two politicians.

Andrzej Duda, the current President of Poland, appears frequently in the Polish memosphere. One of the most often-shared memes associates him with the new government’s flagship initiative, the so-called 500+, a 500 zloty benefit for each additional child in the family. One of the most worn-out phrases in the Polish public sphere, it was instantly attached to a meme in which the President is holding a large baby, appearing to weigh it, with the caption “Well, I’ll be damned! Give 600 zloty for this one.”

Although most of the aforementioned memes refer to Polish politics, and are therefore understandable only to the Poles, there are also some international memes that have a chance to gain a bigger popularity outside of the country. One of the most popular Polish memes was a picture from Barack Obama’s visit to Poland. Before shaking hands with former President of Poland, Bronisław Komorowski, Obama says, “You still have to apply for visas, but we can get you a discount at KFC.” The meme refers to the painful issue of US visas, which is constantly present in the Polish public sphere. The meme has become so famous and widespread in the Polish mass media that KFC has actually started to give a discount using the code “President.”

There may be a dark side to the contemporary Polish enthusiasm for modernity, the internet, and digital culture. The results of an annual survey of reading habits in Poland were published in April 2017, and can be summarized in three numbers: 63-37-10. Sixty-three percent of Poles had not read any books during the previous year. Thirty-seven percent had read at least one, and 10 percent had read 7 or more books. To put this in context, readership has declined internationally as indicated by surveys in the United Kingdom and the United States, particularly for print books, but a Pew Research survey from 2014 indicated that 76% of American adults had read at least one book in the previous year, and the median respondent had read five. The journalist Roman Pawlowski commented on the recent survey of Polish reading habits on his FaceBook profile: “We are, for the most part, a society of functional illiterates, whose ability to put together letters and numbers is restricted to reading supermarket fliers, the banner of the TVP Info and TVN 24 news stations, one-sentence memes, or the SMS from the Party with the daily brief.”

This assessment reflects the decline in the modern viewer’s ability to digest. It is not uncommon to perceive the present-day world as based on high speed and change, and this influences reading habits. Focused reading has been replaced by diffuse reading; and memes, as the briefest form of expression, are often the only reading matter.

Dr. Piotr Marecki was visiting professor in the Skalny Center in Spring 2017. He is assistant professor at the Institute of Culture, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland.