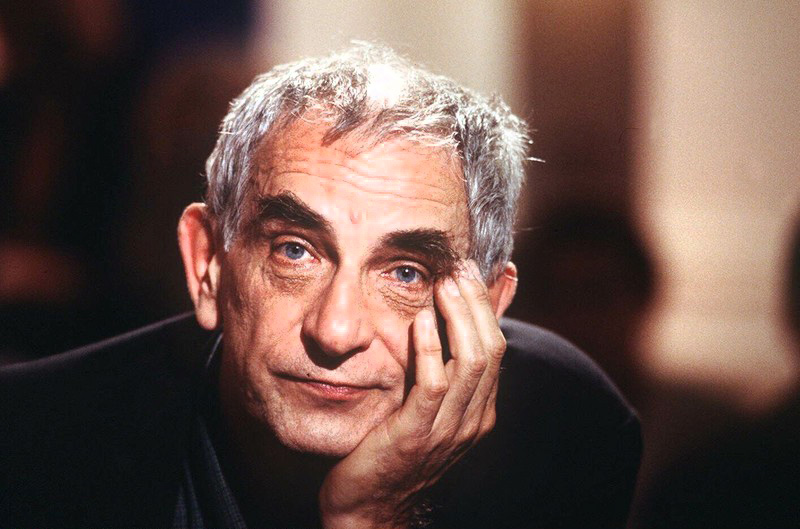

Kieślowski in focus

by Azmina Abdulla

Powerful storytelling, intricate subtlety and dazzling ironies are just a few characteristics to describe Krzysztof Kieslowski’s prolific career as a filmmaker. Kieslowski was a leading director of documentaries, television and feature films from the 1970s to the 1990s, and uniquely humanist in his treatment of contemporary social and moral themes. Marking the twentieth anniversary of his passing, Kieslowski stands today as an emblematic figure of both Polish and European modern cinema at large.

Krzysztof Kieslowski

Early Life

Brought up in a modest Polish family in many small towns and sanatoria in the Regained Territories of Communist Poland, Kieslowski successfully ignited his desire for an education in favor of an early professional career. Very young, he fell in love with the theatre and decided to become a director. In order to enroll in a theatre program, he first had to complete studies in another field. He chose film directing in light of its proximity to theatre, but failed his entrance exams to Lódz Film School two consecutive years. During this time, eager to avoid military service, he starved himself and faked psychological instability, all the while supporting his family through various jobs, from office positions to theatrical tailoring. A true dilettante at heart, he also dabbled in poetry and drawing. After his third attempt, Kieslowski was finally admitted to the school. Founded in 1948 for Stalinist propaganda, the Lódz Film School quickly developed a reputation for its liberal curriculum, which included rare screenings of international cinema and courses in film theory, as well as the production of fiction and documentary films. After this first exposure to international cinema in all its genres and forms, Kieslowski wrote a thesis entitled “Reality and the Documentary Film.” Here he proposed that reality was stranger and more dramatic than fiction, establishing the theoretical platform for the ambiguous relationship between documentary and fiction played out in his films.

Oeuvre

While Lódz had been one of the few Polish towns spared from bombardment during the war, 1968, the year of Kieslowski’s graduation, was a time of heated political dissent and resistance in Poland. Cultural institutions in particular were subject to ideological restrictions, resulting in violently repressed student demonstrations, in which Kieslowski took part. Kieslowski himself battled with the state over his work and experienced a newfound liberty following the end of the Polish People’s Republic. In what can only be described as a decidedly unpromising situation defined by rupture, violence and instability, Kieslowski displayed remarkable powers of continuity in making one astonishing film after another, first in Poland and later in collaboration with Swiss and French production companies. European and Eastern European cinema in particular, is often considered to outwit some limitations imposed by Hollywood, including censorship and cultural subalternity, in producing films defined by inventive visual puzzles and magnificent musical scores, albeit allegories for ideological concepts. Kieslowski’s films are no exception, if not quintessential examples of Polish cinema’s qualities. Borrowing technical cinematographic aspects from the West as a base on which to apply an Eastern style of narrative, Kieslowski created some of the first genuinely multinational aesthetic documents of the European Union.Kieslowski’s oeuvre can be divided into several periods that help to trace his evolution as a filmmaker. First came a documentary period represented by a series of a short films depicting 1960s and 1970s everyday industrial Poland, with titles such as The Tram (Tramwaj) (1966), The Office (Urząd) (1966), Hospital (Szpital) (1976), and Factory (Fabryka) (1971). The ‘60s and ‘70s in Poland were times of great political instability, with feelings of citizenry opposing the propaganda emanating from the state. The media were undergoing risks of censorship, forcing filmmakers to develop a discrete yet intuitive visual language of social critique. At that time, Kieslowski recalled, “there was a necessity, a need—which was very exciting to us—to describe the world. The Communist world had described how it should be and not how it really was.” In parallel, he also produced a series of unrelated narrative features. These features prime his move away from his sole focus on producing documentaries and introduce a narrative critical stance towards contemporary communist Poland. Kieslowski’s transition from a documentarian to a feature filmmaker was never immediate or final. The invasive qualities of documentary became subjugated to the privacy and freedom allowed by narrative; yet the power of historical facts always underlined and to a certain extent, dictated the parameters in which narrative freedom could flourish. Some of the highlights of this period include The Scar (Blizna) (1976) showcasing instances of deforestation for the construction of new factories, ultimately subject to strikes, and Railway Station (Dworzec) (1980), a contextualized portrait of both Warsaw’s Central Railway Station and its visitors.

At the end of the 1980s, a second period is marked by the series The Decalogue (Dekalog) (1988), a ten-part loose examination of the ethical underpinnings of the Ten Commandments. Initially designed as one-hour episodes, each to be directed by a different Polish filmmaker, The Decalogue demonstrates a unique sense of continuity and harmony under Kieslowski’s direction. While each episode explores a different moral and ethical issue, a common ground is established by recurring motifs, including the setting, a large housing project in Warsaw and selected crossovers of characters. Both the subjects and the various mise-en-scène illustrate a novelty in Kieslowski’s style, characterized by a shift from the public to the private, from the uncontrollable realities of the outside world to a calculated and introspective treatment of the domestic space and its inhabitants. An exemplary instance of narrative and visual language overshadowing external realities, The Decalogue series became a critical sensation on the festival circuit and served as the West’s first major exposure to Kieslowski’s work.

Focus: Three Colors trilogy

At the dawn of the new century, Poland was focusing on transitioning to a capitalist society, expanding its connections to the rest of Europe. On the same note, Kieslowski entered a third period in his work in which he took advantage of his growing international notoriety to begin a series of lavish international co-productions with worldwide distribution and much larger budgets than before. Though the films themselves were not overtly political, the contemporary political climate pervaded their context. Already praised for his tight dramatic constructions and emotionally resonant storytelling in The Decalogue (Dekalog) (1988), Kieslowski revised and refined his visual palette in The Double Life of Veronique (1991), followed by his masterpiece, the Three Colors trilogy (Three Colors: Blue in 1993, Three Colors: White in 1993, and Three Colors: Red in 1994).Famous for its intoxicating cinematography and stirring performances by actors such as Juliette Binoche, Julie Delpy, Irène Jacob and Jean-Louis Trintignant, Three Colors examines a group of ambiguously interconnected people experiencing profound personal disruptions. Following the release of The Double Life of Veronique, the Three Colors trilogy embodies a transition in Kieslowski’s visual style, from Polish documentary and fiction to the epitome of the idea of 1990s European art films. This transition coincides with the director’s move from Poland to Paris and the different contexts of productions in the two countries. The fall of Communism in Poland had radically transformed conditions for filmmakers; they were no longer state employees, and funding fell as sharply as the previously clearly defined political and social missions of films. Kieslowski formed part of a group of filmmakers and a trend that witnessed and championed the blurring out of the outlines of national cinema with the exponential rise of co-productions in the advent of the formation of the European Union. Transnationalism was paramount and it translated both in approaches to narration and visual language, that while still rooted in Polish origins became Europeanized – a concept that is clearly highlighted by the Three Colors trilogy, set in Paris, Warsaw, and Geneva, and in which the only references to historical context point to this newly formed European culture.

While Kieslowski’s films are deeply based on the inner struggles of individual protagonists, watching them is arguably more an intellectual and aesthetic experience than an exercise in identification. As Kieslowski famously said: “The goal is to reach that which exists inside the human being, but there are no ways to describe it. You can get closer to it, but you will never reach it. (…) Cinema can’t reach it because it has no means to do so.” In the trilogy, Kieslowski gets close in presenting different intimate portraits within a strong thematic continuum, loosely based on the French flag and the tenets of the French Revolution – liberty, equality, fraternity. Departing from those core themes, the Trilogy unveils as a highly stylized exploration of feelings, in which the individual stories merely become secondary elements rather than an integrated narrative. Moments of narrations become increasingly scarce, replaced by an aesthetic of emotion that brings the visualising experiences to the forefront. The seemingly deeply introspective situations serve as illustrations of existential ideas, windows on a world that should be scrutinized and exposed through cinema.

After Kieslowski completed Red, he announced his retirement at the age of 52. He claimed he was exhausted from having completed the trilogy in a staggered, accelerated time frame and voiced his frustrations at the film medium’s inability to portray the inner life. Despite officially retiring, he continued to sketch plans for another filmic trilogy consisting of Heaven, Hell and Purgatory, inspired by Dante’s The Divine Comedy, until his untimely death in 1996. Twenty years after his death, Krzysztof Kieslowski remains one of Europe’s most influential and acclaimed directors, as well as an infinite source of inspiration and knowledge across borders, genres and generations of filmmakers.

Azmina Abdulla is a student at the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation, Class of 2016, at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.