Bem statue in Budapest

1848 Europe

Congress Poland (1815-74)

Piski Battle

General of the Transylvanian Campaign

Józef Bem Mausoleum in Tarnów

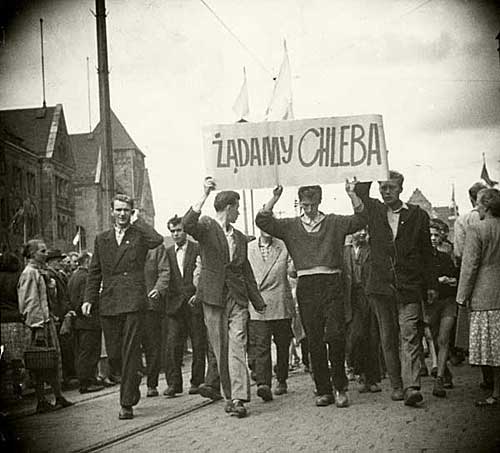

Poznań, June 1956

Budapest, October 1956

Józef Zachariasz Bem was born in 1794, in the small Galician town of Tarnów, in the Carpathian foothills of today’s Poland. At that timeBy 1795, however, there was no Poland, at least not on the map. Geographically vulnerable to rival powers, the once stable Kingdom was partitioned in the 18th Century among expansionary rivals of Prussia, Russia and Habsburg Austria. Although briefly resurrected during the Napoleonic wars, as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, it quickly faded as the French went down in defeat.

Following the 1815 Congress of Vienna, a small parcel of Polish land was defined as Congress Poland, but it was subjugated to Russia. Sadly torn, Poles kept faith and made repeated attempts to reclaim thetheir homeland. A significant uprising took place in the winter/spring of 1830-31, when Polish patriots fought imperial Russia.

As a young man, Bem received military training, participated in the closing phase of Napoleon’s campaign, and subsequently took up teaching mathematics at a military college. In November 1830 he quickly joined the uprising, was given a major's commission and the command of a Light Cavalry Battalion, which he led during the Battles of Iganie and Ostrołęka. In this valiant fight, Polish patriots were outnumbered 10:1 and had no hope of getting outside help. When it was over, harsh Russian reprisals forced a wave of émigrés, most of whom fled to France. Bem was among them, joined in fate by composer Chopin, the poet Adam Mickiewicz, geologist-educator Ignacy Domeyko, and many others. To make ends meet in exile, Bem took up teaching, and published his memoiresmemoirs on the Polish Uprising where, in which he formulated specific plans to resurrectfor the next attempt to liberate Poland. The essence of post-Napoleonic Europe, as defined by the Congress of Vienna, was a framework established by the conservative rulers to preserve the social order. They called it the Holy Alliance, where rebellion was out, kings, monarchs and nobility were in. An uprising anywhere was cause enough to intervenefor intervention by all participating powers. But there were cracks in this Order. In 1830, as mentioned, and most notably in 1848, this conservative order was shaken.

1848, The Sping of Nations

The spring of 1848 witnessed numerous uprisings. Starting in Paris, they quickly spread to the Italian lands, the German states, and Habsburg dominions. The subject clearly deserves a separate discussion, but the intent here is to concentrate on the Habsburg Empire, where Vienna erupted on March 13, and Pest on March 15. A young poet, Sándor Petőfi, led the revolution in Pest. Citizens’ demands were compiled into 12 Points that included freedom of press, of assembly, the abolition of serfdom, eradication of the nobility’s tax-privileges and judicial equality. These were submitted to the National Assembly in Pozsony-Pressburg, then to Emperor Ferdinand, also King of Hungary, in Vienna. His Majesty hastily agreed to eveything, partly because Vienna also had just erupted in sympathy with events in Hungary, while the Austrian army, commanded by Prince Windisch-Grätz, was away putting down yet another rebellion in Italy. The reforms that went into effect in Hungary were called the April Laws. People were exuberant as this looked like a huge victory. While continuing to recognize the House of Habsburg as sovereign, Hungary was now free to excercise home rule and eradicate an archaic feudal order, joining westernWestern countries in free commerce and industrialization.

Alas, the euphoria did not last long. Prince Windisch-Grätz prevailed in Italy, the army was returning to restore order in Vienna and elsewhere. The king was focedforced to abdicate in favor of his nephew, 18 yr old Franz Joseph, who back-dancedreneged on most of the concessions, and in effect nullified the April Laws. This in turn escalated into a full blown confrontation.

During these exciting events, Bem sensed the opportunity and first came to Vienna to help the insurgents hold the city against the returning army of Windisch-Grätz. When this was no longer possible, he moved on to Pozsony and offered his services to Louis Kossuth, Governor of Hungary. In him, Kossuth just simply got the best there was.

Immediately, Bem was given the challenge to secureof securing Transylvania from occupying imperial forces. It was no small task. He took command at the end of ‘48, with only a few thousand men. On Christmas Day he entered Kolozsvár (Cluj) and enthusiastic new volunteers kept joining. Then, in early ‘49, as General of the Székely troops, he performed miracles with his little army, most notably at the bridge of Piski on February 9, where, after fighting all day, he drove back a much larger mercenary force. This was a pivotal battle as it not only turned the tide but set the tone of his fighting style.

As a professional soldier, Bem was remarkable for his excellent handling of artillery and the rapidity of his marches. He used precise mathematical calculations to project troop movements and artillery range. He was also a master at deception, using cover, concealment and bluffbluffing when it was tactically advantageous. He had to use these skills, because he was always the underdog, but his skill made up for the lack of military might at his disposal. As a man, he was respected for his courage and heroic temper, both of which were in contrast with his otherwise small stature. He was strict, yet fair to his officers and men. His influence is said to have been magnetic. Although none of his Székely subordinates understood the language he spoke, most revered him. The poet Petőfi was under his command as a captain. They spoke French with each other. He deeply respected his general,; theirs resembled a father-son relationship.

By late May 1849, imperial Austrian forces were beatenhad been driven out of Hungary, including Transylvania. At this point, the Habsburg House played the Holy Alliance card. The Emperor formally asked the Tsar of Russia to intervene. As a result, a fresh Russian invasion force of 300 thousand men entered in July on the Transylvanian side. Bem was directly facing the same General Ivan Paskevich he had once fought at Ostrołęka. A desperate delaying action followed, but being because Bem’s forces were so greatly outnumbered, it was no longer a contest. On July 31, Bem’s army was beaten at Segesvár, where Petőfi perished, and Bem also was seriously wounded. Within days, the valiant fight for Hungary’s independence collapsed. Reprisals were quick and harsh,: 13 Hungarian generals faced the gallows on October 6, 1849, while the entire nation went into mourning.

Bem managed to flee to the south, then part of the Ottoman Empire. He offered his services to the Sultan, and in the process adopted Islam. He served as Governor of Aleppo under the name of Murad Pasha. Converting to Islam was necessary to prevent extradition, since Russia & and Austria both wanted him, and also to obtain a commission. His lifelong mission was to fight on behalf of whoever opposed Russia, the foremost oppressor of his people. In 1850, he fell victim to an epidemic, and his last words were, “My beloved Poland, I will not be the one to liberate you!”.

His legacy is alive in Poland, Hungary and Transylvania. In 1929, his earthly remains were repatriated from Turkey to Poland and laid to rest in Tarnów.

His statue in Buda is where the next Hungarian Revolution began on October 23, 1956, organized by students of Budapest Technical University, in solidarity with workers of Poznan, who made a brave stand against Communist oppression earlier that year. In turn, the first shipment of blood plasma came from Poznan.

Polish-Hungarian friendship enjoys a long tradition, nurtured by historical similarity and similar fate. In this, the life of Józef Bem is a presciousprecious mosaic. His tireless dedication transcends our Central European setting, as the cause of Liberty is truly universal, as it is timeless.

Luis I. Nagy is Executive Secretary, Hungarian-American Club of Rochester